Validation Parameters for Spectroscopic Methods: A Complete Guide for Researchers and Drug Development Professionals

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the validation of spectroscopic analytical methods, a critical process for ensuring data reliability in pharmaceutical development and biomedical research.

Validation Parameters for Spectroscopic Methods: A Complete Guide for Researchers and Drug Development Professionals

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the validation of spectroscopic analytical methods, a critical process for ensuring data reliability in pharmaceutical development and biomedical research. It covers foundational principles by explaining core validation parameters as defined by ICH, FDA, and other regulatory bodies. The guide delves into methodological applications across key spectroscopic techniques including FT-IR, Raman, and UV-Vis, with practical strategies for sample preparation and data acquisition. It also addresses common troubleshooting scenarios and optimization techniques for complex analyses. Finally, the article outlines structured protocols for performing full method validation, comparative technology assessment, and preparing for regulatory audits, equipping scientists with the knowledge to build robust, compliant analytical methods.

Core Principles and Regulatory Landscape of Spectroscopic Method Validation

In the pharmaceutical and life sciences industries, the integrity and reliability of analytical data are the bedrock of quality control, regulatory submissions, and ultimately, patient safety [1]. Analytical method validation (MV) is the formal, documented process of proving that an analytical procedure is acceptable for its intended purpose, ensuring that every future measurement in routine analysis will be sufficiently close to the unknown true value of the analyte in the sample [2]. For multinational drug developers, navigating a patchwork of regional regulations could be a logistical nightmare. This challenge is addressed by harmonized guidelines from the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH), which provide a global gold standard that, once adopted by member regulatory bodies like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), ensures a method validated in one region is recognized and trusted worldwide [1]. This guide objectively compares validation approaches and instrumentation through the lens of contemporary spectroscopic practices, providing researchers with the experimental protocols and data needed to ensure excellence in pharmaceutical development.

The Regulatory and Scientific Framework

Core Principles and Guidelines

The necessity for laboratories to use fully validated methods is universally accepted as a pathway to reliable results [2]. The ICH provides the primary framework through its quality guidelines, most notably ICH Q2(R2) on the "Validation of Analytical Procedures" and the newer ICH Q14 on "Analytical Procedure Development" [1]. The 2025 update to ICH Q2(R2) modernizes the principles from its predecessor by expanding its scope to include modern technologies and emphasizing a science- and risk-based approach [3] [1]. A significant shift embodied in these updates is the move from a one-time validation event to a continuous lifecycle management model, where method validation begins with development and continues throughout the method's entire operational life [1].

The Challenge of Terminology and Parameters

A critical challenge in method validation is the lack of universal terminology. Numerous national and international guidelines contain discrepant and controversial information, which can generate confusion during the validation process [2]. For instance, the terms "accuracy" and "trueness" are often used interchangeably, and "selectivity" and "specificity" have overlapping definitions across different guidelines [2]. An analysis of 37 different validation guidelines found that precision is the most frequently included parameter (97%), followed by limit of detection (92%), and selectivity/specificity (89%) [2]. Researchers must therefore clearly specify the guideline they are following when validating a method.

Critical Validation Parameters for Spectroscopic Methods

The validation of a spectroscopic method requires a thorough investigation of several key performance characteristics. The following table summarizes the core parameters as defined by ICH guidelines and applied in contemporary research.

Table 1: Core Validation Parameters for Spectroscopic Methods Based on ICH Q2(R2)

| Parameter | Definition | Typical Acceptance Criteria | Experimental Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | The closeness of agreement between the test result and the true value. [1] | Recovery of 98–102% for API | Compare results to a reference standard or spike recovery study. [1] |

| Precision | |||

| (Repeatability) | The closeness of agreement under the same operating conditions over a short period. [1] | RSD < 2% for API | Multiple measurements of a homogeneous sample. [4] [1] |

| Specificity | The ability to assess the analyte unequivocally in the presence of other components. [1] | No interference from excipients or impurities | Compare analyte response in presence and absence of potential interferents. [4] |

| Linearity | The ability to obtain test results proportional to the concentration of the analyte. [1] | Correlation coefficient (r) > 0.998 | Analyze a series of standard solutions across the claimed range. [4] |

| Range | The interval between the upper and lower concentrations for which linearity, accuracy, and precision are demonstrated. [1] | Established from linearity data | Derived from the linearity study. |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | The lowest amount of analyte that can be detected. [1] | Signal-to-noise ratio of 3:1 | Based on signal-to-noise ratio or standard deviation of the response. |

| Limit of Quantification (LOQ) | The lowest amount of analyte that can be quantified with acceptable accuracy and precision. [1] | Signal-to-noise ratio of 10:1; RSD < 5% for accuracy/precision | Based on signal-to-noise ratio or standard deviation of the response and a suitable accuracy/precision study. |

| Robustness | A measure of the method's capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters. [1] | No significant impact on system suitability | Deliberate variation of parameters (e.g., pH, wavelength). [4] |

Advanced Considerations in Detection and Quantification

Beyond the basic LOD and LOQ definitions, the concept of a "detection limit" has nuances. Research on Ag-Cu alloys using X-ray fluorescence (XRF) highlights that various detection limits exist, including the Lower Limit of Detection (LLD), Instrumental Limit of Detection (ILD), and Minimum Detectable Limit (CMDL), each with slightly different statistical definitions and confidence levels [5]. This study demonstrated that the sample matrix composition significantly affects detection limits, a critical factor for drug formulations with complex excipient profiles [5]. For example, in the XRF analysis of alloys, the detection limits for silver and copper varied considerably depending on the composition of the Ag-Cu matrix, emphasizing the need for careful consideration of matrix effects during method validation [5].

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

Case Study: UV Spectroscopic Method for Gepirone HCl

A 2025 study details the development and validation of a UV spectroscopic method for estimating Gepirone Hydrochloride in dissolution media, providing a practical template for researchers [4]. The experimental workflow is outlined below.

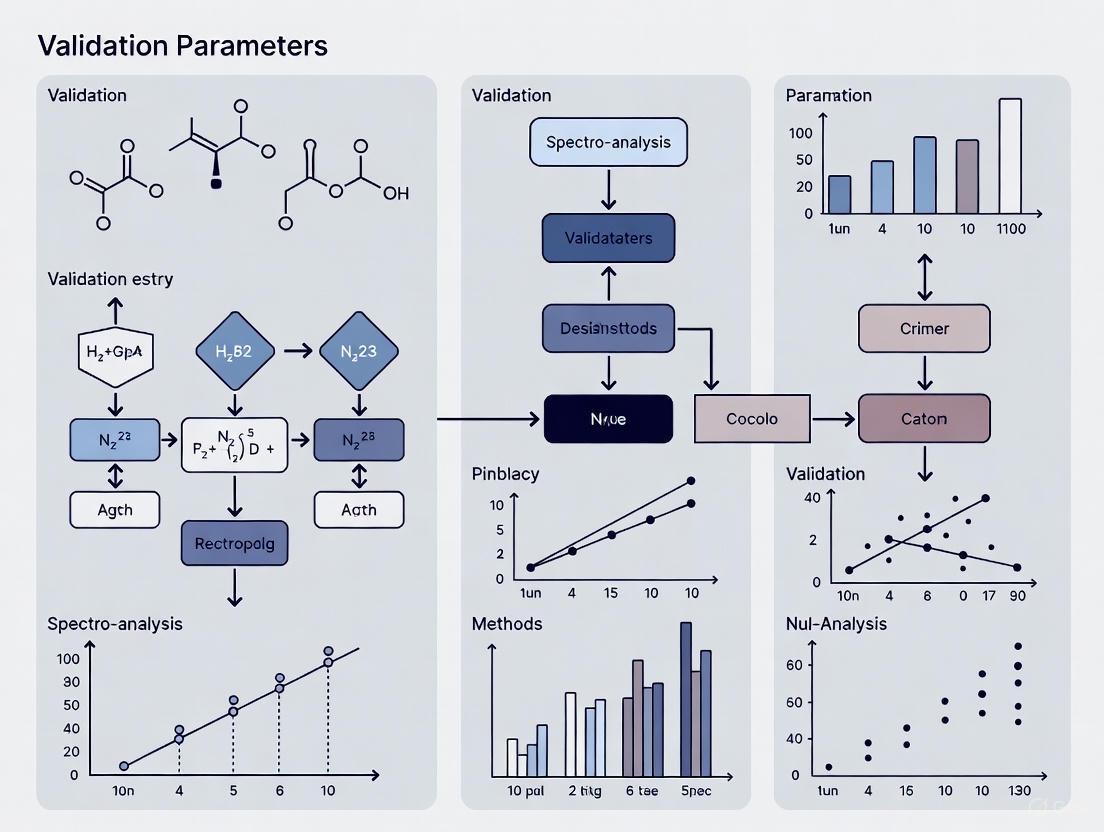

Diagram 1: UV Method Validation Workflow. This workflow outlines the key experimental stages for validating a UV spectroscopic method, from initial setup to final approval. R²: coefficient of determination.

Detailed Experimental Methodology

- Instrumentation and Reagents: The analysis was performed using a double-beam UV-Visible spectrophotometer. The pure drug substance was used to prepare stock solutions in the dissolution media, 0.1N HCl and phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) [4].

- Linearity and Range: Standard solutions were prepared across a concentration range of 2–20 μg/mL. Absorbance was measured at the respective λmax (233 nm in 0.1N HCl and 235 nm in pH 6.8 buffer), and a calibration curve was constructed by plotting absorbance versus concentration [4].

- Accuracy (Recovery): To confirm accuracy, a placebo formulation (lacking the active drug) was spiked with known quantities of the Gepirone HCl standard at three different concentration levels (80%, 100%, and 120% of the target concentration). The percent recovery of the drug was then calculated, demonstrating high accuracy [4].

- Precision: Precision was validated at two levels:

- Specificity: Specificity was confirmed by analyzing a placebo solution. The absence of any absorption signal at the λmax of the drug confirmed that the excipients did not interfere with the quantification of the active ingredient [4].

- Robustness: The method's robustness was evaluated by introducing small, deliberate changes to experimental conditions, such as slight variations in the pH of the buffer. The results were unaffected by these minor alterations, proving the method is robust [4].

The Comparison of Methods Experiment

For assessing the inaccuracy or systematic error of a new method against an existing one, a comparison of methods experiment is critical [6]. The guidelines for this experiment are:

- Specimens: A minimum of 40 different patient specimens should be tested, selected to cover the entire working range of the method. Using 100-200 specimens is recommended to thoroughly assess specificity and interference [6].

- Time Period: The experiment should span several analytical runs on different days, with a minimum of 5 days recommended to minimize systematic errors from a single run [6].

- Data Analysis: Data should be graphed, typically as a difference plot (test result minus comparative result vs. comparative result) or a comparison plot (test result vs. comparative result). Linear regression statistics (slope, y-intercept, standard error) are then used to estimate systematic error at medically important decision concentrations [6].

Comparative Performance of Spectroscopic Techniques

The landscape of spectroscopic instrumentation is rapidly evolving, with a clear trend toward miniaturization, automation, and specialized detection. The 2025 Review of Spectroscopic Instrumentation reveals distinct performance characteristics for different techniques [7].

Table 2: Comparison of Advanced Spectroscopic Instrumentation (2024-2025)

| Technique | Example Instrument (Vendor) | Key Performance Features | Intended Application & Comparative Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| FT-IR Spectrometry | Vertex NEO Platform (Bruker) [7] | Vacuum optical path removes atmospheric interference; multiple detector positions. [7] | Lab-based analysis of proteins and far-IR studies. Advantage: Superior for removing atmospheric interferences compared to standard FT-IR. |

| QCL Microscopy | LUMOS II ILIM (Bruker) [7] | QCL source; imaging rate of 4.5 mm²/s; reduced speckle. [7] | Microspectroscopy for material science. Advantage: Faster imaging and better image quality vs. traditional globar-source IR microscopes. |

| Handheld NIR | OMNIS NIRS Analyzer (Metrohm) [7] | Nearly maintenance-free; simplified method development. [7] | Field-based quality control. Advantage: Portability and ease-of-use compared to lab-bound benchtop NIR analyzers. |

| A-TEEM Spectroscopy | Veloci Biopharma Analyzer (Horiba) [7] | Simultaneous Absorbance-Transmittance-Fluorescence (EEM) data. [7] | Biopharmaceuticals (mAbs, vaccines). Advantage: Provides multi-dimensional data as an alternative to traditional separation methods. |

| Handheld Raman | TaticID-1064ST (Metrohm) [7] | 1064 nm laser; onboard camera and note-taking. [7] | Hazardous material ID. Advantage: 1064 nm laser reduces fluorescence interference compared to 785 nm handheld Raman. |

| Microwave Spectroscopy | Broadband CP-MS (BrightSpec) [7] | Unambiguous determination of gas-phase molecular structure. [7] | Academic/Pharma R&D. Advantage: Provides definitive structural data that is complementary to MS and NMR. |

Trends in Pharmaceutical Analysis

The integration of spectroscopy with other techniques is a powerful trend. Hyphenated analytical platforms, such as LC-MS and GC-MS, are invaluable for the de novo identification, quantification, and authentication of complex constituents in natural products and pharmaceuticals [8]. Furthermore, the industry is moving towards Real-Time Release Testing (RTRT), which shifts quality control to in-process monitoring using Process Analytical Technology (PAT), often employing inline spectroscopic tools to accelerate product release without compromising quality [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and materials are fundamental for conducting spectroscopic analytical method validation in a pharmaceutical context.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Spectroscopic Method Validation

| Reagent / Material | Function in Validation | Critical Quality Attributes |

|---|---|---|

| Ultrapure Water | Sample preparation, dilution, and mobile phase/ buffer preparation. | Defined resistivity (e.g., 18.2 MΩ·cm at 25°C), low TOC, and endotoxin levels. [7] |

| Certified Reference Standards | Used to establish accuracy, linearity, and precision. Provides the "true value" for comparison. | High purity (>98.5%), certified concentration, and traceability to a primary standard. [1] |

| Placebo Formulation | Used in specificity and recovery studies to confirm the absence of interference from excipients. | Must be identical to the final drug product formulation, minus the active ingredient. [4] |

| Phosphate Buffers & 0.1N HCl | Common dissolution media and solvent systems for UV spectroscopic method development. | Precise pH (±0.05 units), specified buffer capacity, and filtered to remove particulates. [4] |

Analytical method validation is not a regulatory hurdle but a fundamental scientific activity that ensures the generation of reliable data, which is the currency of drug development. The process, guided by ICH Q2(R2) and Q14, has evolved into a lifecycle approach that begins with a clear definition of the method's purpose in the form of an Analytical Target Profile (ATP) [1]. As spectroscopic technologies advance—becoming more portable, sensitive, and integrated—the principles of validation remain constant, even as the experimental details adapt. A robustly validated spectroscopic method, whether a simple UV assay for dissolution testing or a sophisticated QCL microscope for structural analysis, provides the confidence needed to make critical decisions on drug safety, efficacy, and quality, ultimately protecting patient health and accelerating the delivery of new therapies to the market.

Analytical method validation provides documented evidence that a laboratory test is reliable, consistent, and suitable for its intended purpose. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding core validation parameters is fundamental to ensuring the quality of data supporting product development and regulatory submissions. This guide examines these key parameters through a comparative lens, using experimental data to illustrate how they are applied across different analytical techniques.

Core Validation Parameters Explained

Validation parameters are standardized criteria defined by guidelines such as the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) Q2(R2) to ensure analytical methods are fit-for-purpose [9]. These parameters collectively form a framework for proving that a method produces results that are accurate, reliable, and meaningful.

Specificity/Selectivity: The ability of a method to measure the analyte accurately and specifically in the presence of other components that may be expected to be present in the sample matrix [10] [9]. It ensures the method is free from interference from other active ingredients, excipients, impurities, or degradation products.

Accuracy: The closeness of agreement between a conventionally accepted true value (or an accepted reference value) and the value found in a sample [10]. It is typically reported as the percentage recovery of the known, added amount of analyte [11].

Precision: The closeness of agreement (degree of scatter) between a series of measurements obtained from multiple sampling of the same homogeneous sample under the prescribed conditions [10]. It is generally considered at three levels:

- Repeatability (intra-assay precision): Precision under the same operating conditions over a short interval of time [10].

- Intermediate Precision: Precision within the same laboratory, accounting for variations like different days, analysts, or equipment [10].

- Reproducibility: Precision between different laboratories [10].

Linearity and Range: Linearity is the ability of the method to obtain test results that are directly proportional to the analyte concentration within a given range [10]. The Range is the interval between the upper and lower concentrations of analyte for which suitable levels of precision, accuracy, and linearity have been demonstrated [11] [10].

Limit of Detection (LOD) and Limit of Quantitation (LOQ): The LOD is the lowest amount of analyte in a sample that can be detected, but not necessarily quantitated, as an exact value. The LOQ is the lowest amount of analyte that can be quantitatively determined with suitable precision and accuracy [10]. These are often determined via signal-to-noise ratios, typically 3:1 for LOD and 10:1 for LOQ [10].

Robustness: A measure of a method's capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters (such as pH, mobile phase composition, or temperature) and provides an indication of its reliability during normal usage [11] [9].

Comparative Analysis of Spectroscopic and Chromatographic Methods

A direct comparison of validation parameters for different techniques highlights their relative strengths and weaknesses. The following table summarizes validation data from a study that developed and validated methods for quantifying piperine in black pepper using Ultraviolet (UV) spectroscopy and High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) [12] [13].

Table 1: Comparison of Validation Parameters for UV Spectroscopy and HPLC in Piperine Analysis

| Validation Parameter | UV Spectroscopy Method | HPLC Method |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity | Good specificity [12] [13] | Good specificity [12] [13] |

| Linearity | Good linearity [12] [13] | Good linearity [12] [13] |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | 0.65 [12] [13] | 0.23 [12] [13] |

| Accuracy (Recovery) | 96.7% to 101.5% [12] [13] | 98.2% to 100.6% [12] [13] |

| Precision (% RSD) | 0.59% to 2.12% [12] [13] | 0.83% to 1.58% [12] [13] |

| Measurement Uncertainty | 4.29% (at 49.481 g/kg) [12] [13] | 2.47% (at 34.819 g/kg) [12] [13] |

The data demonstrates that while both methods performed well, HPLC was more sensitive (lower LOD) and more accurate (lower measurement uncertainty) than UV spectroscopy for this specific application [12] [13]. This kind of comparative data is crucial for selecting the most efficient method for a given analytical problem.

Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Experiments

To ensure reliable results, validation experiments must be conducted following rigorous, predefined protocols. Below are generalized methodologies for assessing core validation parameters, adaptable to various analytical techniques.

Protocol for Determining Accuracy

Accuracy is typically established by analyzing samples (drug substance or product) spiked with known quantities of the target analyte [10] [9].

- Procedure:

- Prepare a blank sample (matrix without the analyte).

- Prepare a minimum of nine determinations over a minimum of three concentration levels (e.g., low, medium, high) covering the specified range of the procedure. This means three replicates at each of the three concentrations [10].

- Analyze the samples using the validated method.

- Calculate the recovery (%) for each sample using the formula:

(Measured Concentration / Known Concentration) * 100.

- Acceptance: Data is reported as the percentage recovery of the known, added amount. The mean recovery should be within the predefined acceptance criteria [10].

Protocol for Determining Precision

Precision is measured as repeatability (intra-assay) and intermediate precision [10].

- Procedure for Repeatability:

- Analyze a minimum of nine determinations covering the specified range (e.g., three concentrations, three replicates each) or a minimum of six determinations at 100% of the test concentration [10].

- Perform all analyses under identical conditions (same analyst, same instrument, short time interval).

- Calculate the Relative Standard Deviation (RSD or %RSD) of the results.

- Procedure for Intermediate Precision:

- Have a second analyst repeat the repeatability experiment on a different day, using a different instrument (if available), and preparing their own standards and solutions [10].

- The results from both analysts are subjected to statistical comparison (e.g., a Student's t-test) to examine if there is a significant difference in the mean values obtained.

Protocol for Determining LOD and LOQ

The LOD and LOQ can be determined based on the standard deviation of the response and the slope of the calibration curve [10].

- Procedure:

- Prepare a series of very low concentration samples near the expected detection limit.

- Analyze these samples and measure the response.

- Calculate the standard deviation (SD) of the response and the slope (S) of the calibration curve.

- Calculate LOD and LOQ using the formulas:

LOD = 3.3 * (SD / S)LOQ = 10 * (SD / S)

- Verification: Once calculated, an appropriate number of samples should be analyzed at the LOD and LOQ levels to confirm the method's performance at these limits [10].

Protocol for Determining Linearity and Range

Linearity is established by analyzing samples across a defined range of concentrations [10] [9].

- Procedure:

- Prepare a minimum of five concentration levels covering the specified range of the method [10].

- Analyze each concentration level.

- Plot the measured response (e.g., peak area) against the known concentration.

- Perform a linear regression analysis on the data. The coefficient of determination (r²) is a key indicator of linearity.

- Acceptance: The method is considered linear if the r² value meets the acceptance criteria (e.g., ≥ 0.990) [9]. The range is the interval between the lowest and highest concentrations for which linearity, accuracy, and precision have been demonstrated.

Visualizing the Method Validation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and workflow between the key validation parameters.

Research Reagent Solutions for Validation

A successful validation study requires high-quality materials and reagents. The following table details essential items and their functions in the context of developing and validating an analytical method.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Analytical Method Validation

| Item | Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Material (CRM) | Serves as an accepted reference standard with a conventionally true value to establish method accuracy [14]. |

| High-Purity Solvents (e.g., Traceselect) | Used for sample preparation and mobile phases to minimize background interference and noise, critical for achieving low LOD/LOQ [14]. |

| Chromatography Columns (e.g., C18) | The stationary phase for HPLC separation; critical for achieving specificity by resolving the analyte from impurities [15] [16]. |

| Buffer Salts (e.g., Ammonium Acetate) | Used to prepare mobile phases and control pH, which can significantly impact retention time, peak shape, and method robustness [15]. |

| Ultrapure Water (e.g., Milli-Q) | Used for preparing solutions and blanks; its high resistivity (>18 MΩ·cm) prevents contamination that could affect accuracy and precision [14]. |

| Dedicated pH Meter | Essential for the accurate preparation of buffer solutions, a key factor in ensuring the robustness and reproducibility of the method [9]. |

The validation parameters of accuracy, precision, specificity, LOD, LOQ, linearity, and range are interdependent pillars of a reliable analytical method. As demonstrated by the comparative data, the choice of analytical technique significantly impacts method performance. HPLC offered superior sensitivity and lower measurement uncertainty for piperine analysis, while UV spectroscopy provided a simpler, faster, and more environmentally friendly alternative [12] [15]. Researchers must therefore balance performance requirements with practical considerations. A thorough understanding of these parameters and adherence to structured experimental protocols are non-negotiable for generating data that ensures product quality, patient safety, and regulatory compliance.

In the pharmaceutical industry, ensuring the quality, safety, and efficacy of drug products is paramount. This assurance is governed by a complex framework of regulatory guidelines and pharmacopoeial standards that define requirements for drug development, manufacturing, and quality control. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the interplay between these guidelines—particularly those issued by the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH), the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the United States Pharmacopeia (USP), and the European Pharmacopoeia (EP)—is essential for successful regulatory compliance and global market access. These frameworks establish the foundational principles for analytical procedure validation, with specific applications to spectroscopic methods which are critical tools in pharmaceutical analysis.

The harmonization of these requirements remains an ongoing challenge and priority for the global pharmaceutical community. Organizations like the Pharmacopoeial Discussion Group (PDG), formed in 1989, work to harmonize excipient monographs and general chapters across the USP, EP, and Japanese Pharmacopoeia (JP) to reduce the burden on manufacturers who would otherwise need to perform analytical procedures differently for each jurisdiction [17]. Similarly, the International Meeting of World Pharmacopoeias (IMWP), convened by the World Health Organization, fosters international cooperation and promotes the development of global standards for medicines [17]. Understanding both the distinct requirements and collaborative efforts between these organizations provides scientists with a strategic advantage in designing robust analytical methods, particularly for spectroscopic applications in pharmaceutical quality assurance and quality control.

Comparative Analysis of Regulatory Bodies and Pharmacopoeias

The regulatory landscape for pharmaceuticals is structured with distinct yet complementary roles for international harmonization bodies, regulatory authorities, and pharmacopoeial standard-setting organizations. The ICH develops broad, scientific consensus-based guidelines that establish universal principles for pharmaceutical development and registration. Regulatory agencies like the FDA implement and enforce these standards within their legal jurisdictions, while pharmacopoeias such as USP and EP provide the detailed, practical testing methodologies and acceptance criteria that demonstrate compliance. The following table provides a structured comparison of these key organizations.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Pharmaceutical Regulatory and Standards Organizations

| Organization | Type & Governance | Primary Role & Scope | Key Documents/Standards | Legal Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICH (International Council for Harmonisation) | International consortium of regulatory authorities & pharmaceutical industry [17] | Develops harmonized technical guidelines for drug registration to ensure safe, effective, high-quality medicines [17] | Q2(R2): Validation of Analytical Procedures; Q14: Analytical Procedure Development [18] | Not legally binding itself, but implemented into regional law by members (e.g., FDA, EMA) |

| FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration) | U.S. federal regulatory agency [18] | Protects public health by ensuring human drugs are safe and effective; enforces USP standards [18] [19] | 21 CFR Part 211: Current Good Manufacturing Practice; Various Guidance Documents (e.g., PAT) [20] | Legally enforceable regulations in the United States |

| USP (United States Pharmacopeia) | Independent, non-profit scientific organization [19] [21] | Sets public compendial standards for drugs, dietary supplements, and food ingredients in the U.S. and over 140 countries [19] | USP-NF (United States Pharmacopeia – National Formulary); General Chapters (e.g., <1225>, <1058>) [22] [21] | Enforceable by the FDA under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act [19] |

| EP (European Pharmacopoeia) | Treaty-based organization under the Council of Europe (EDQM) [17] [19] | Provides legally binding quality standards for medicinal products in its member states [17] [19] | European Pharmacopoeia (Ph. Eur.); General Chapters (e.g., 2.4.24 on Residual Solvents) [23] | Legally binding in member states of the Council of Europe and the European Union [19] |

Analytical Procedure Validation: ICH Q2(R2) and Pharmacopoeial Application

The ICH Q2(R2) guideline, titled "Validation of Analytical Procedures," provides the fundamental framework for demonstrating that an analytical method is suitable for its intended purpose [18]. This guideline outlines key validation parameters that must be established for a method, covering aspects such as accuracy, precision, specificity, and linearity. The recent update in March 2024 reinforces these principles and explicitly extends them to cover advanced analytical techniques, including the spectroscopic use of data [18]. This makes ICH Q2(R2) the cornerstone document for validating spectroscopic methods in pharmaceutical analysis.

Pharmacopoeias like USP and EP operationalize these ICH principles into concrete testing procedures and acceptance criteria. The USP general chapter <1225> "Validation of Compendial Procedures" is a direct application of ICH Q2(R1) and, by extension, the updated Q2(R2) principles, providing detailed guidance on how to validate various types of analytical methods [21]. Similarly, the EP incorporates these validation requirements into its general chapters and monographs. For spectroscopic methods, this means that the fundamental validation parameters are globally harmonized through ICH, while the specific methodological details and system suitability tests may be described in the respective pharmacopoeia. The following diagram illustrates the hierarchical relationship between these documents and the core validation parameters for spectroscopic methods.

Diagram 1: Regulatory Hierarchy for Analytical Method Validation

Spectroscopic Methods in Pharmaceutical QA/QC: Validation and Application

Spectroscopic techniques are indispensable in pharmaceutical quality assurance and control (QA/QC) due to their precision, reproducibility, and non-destructive nature [20]. These methods provide critical data on the identity, strength, purity, and composition of drug substances and products throughout development and manufacturing. The application of UV-Vis, IR, and NMR spectroscopy is well-established and recognized by regulatory bodies when methods are properly developed, validated, and documented according to ICH, USP, and EP standards [20].

Key Spectroscopic Techniques and Their Regulatory Applications

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) Spectroscopy: This technique measures the absorbance of light in the 190–800 nm range, corresponding to electronic transitions in molecules. In QA/QC, its primary strengths are rapid quantification and high-throughput analysis. Regulatory applications include ensuring consistent concentration of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs), content uniformity testing in solid dosage forms, impurity monitoring, and assessing dissolution profiles during stability studies [20]. Its validation focuses heavily on accuracy, linearity, and range for quantitative analysis.

Infrared (IR) Spectroscopy: IR spectroscopy detects vibrational transitions of molecules, creating a unique "fingerprint" based on functional groups. It is predominantly used for qualitative identity testing. A key regulatory application is the identification of raw materials, where the sample spectrum must match that of a reference standard. It is also crucial for detecting subtle structural differences, such as polymorphic forms in APIs, which can affect a drug's bioavailability and stability [20]. Validation for IR methods emphasizes specificity above all else.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: NMR provides unparalleled detail on molecular structure, dynamics, and stereochemistry by probing the magnetic properties of atomic nuclei. In pharmaceutical analysis, it is indispensable for structural elucidation of complex molecules and impurity profiling, as it can identify and quantify structurally related compounds at trace levels. Quantitative NMR (qNMR) is increasingly used as a primary method for determining the absolute potency and purity of reference standards [20]. NMR method validation requires demonstrating high specificity and robustness.

Table 2: Spectroscopic Methods in Pharmaceutical QA/QC: Applications and Validation Focus

| Technique | Primary QA/QC Applications | Key Validation Parameters per ICH Q2(R2) | Sample Preparation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis Spectroscopy | - API concentration determination- Content uniformity testing- Dissolution testing- Impurity monitoring | - Accuracy & Precision (quantification)- Linearity & Range- Specificity | - Requires optically clear solutions- Must use compatible solvents- Absorbance within linear range (0.1-1.0 AU) [20] |

| IR Spectroscopy | - Raw material identity testing- Polymorph screening- Verification of compound structure- Contaminant detection | - Specificity (primary focus)- Precision (if quantitative) | - Solids: KBr pellets or ATR- Liquids: ATR or transmission cells- Avoid atmospheric CO₂ & moisture [20] |

| NMR Spectroscopy | - Structural elucidation & confirmation- Impurity profiling & identification- Quantitative analysis (qNMR)- Stereochemical verification | - Specificity- Accuracy (for qNMR)- Linearity (for qNMR)- Robustness | - Requires deuterated solvents (e.g., CDCl₃, DMSO-d₆)- Sample must be free of particulates- Optimized concentration for signal-to-noise [20] |

Experimental Protocol: System Suitability and Method Verification for Spectroscopic Analysis

A critical component of maintaining regulatory compliance in spectroscopic analysis is the execution of system suitability testing and ongoing method verification. The following workflow, based on USP <621> and ICH Q2(R2) requirements, outlines a standard protocol for ensuring an analytical system is performing adequately before and during use [20] [21].

Diagram 2: System Suitability Testing Workflow

Protocol Details:

Instrument Qualification and Calibration: As per USP <1058>, the analytical instrument (spectrometer) must have a documented and current status for Installation Qualification (IQ), Operational Qualification (OQ), and Performance Qualification (PQ) [21]. Calibration of sensors, such as wavelength verification for UV-Vis and chemical shift referencing for NMR, must be performed prior to analysis [20].

Preparation of System Suitability Solution: A solution containing the target analyte or a subset of analytes from the method is prepared from a certified reference standard. For example, a revised EP chapter on residual solvents (2.4.24) specifies the use of "a separate system suitability solution prepared from a subset of Class 2 solvents" [23].

Data Acquisition and Evaluation: The system suitability solution is analyzed using the validated spectroscopic method. The resulting data is evaluated against pre-defined acceptance criteria. For quantitative UV-Vis methods, this may include parameters like signal-to-noise ratio for Limit of Detection (LOD) and Quantitation (LOQ). For identity-testing IR methods, the critical parameter is the spectral match to a reference spectrum.

Action Based on Results: If all system suitability criteria are met, the analysis of actual samples may proceed. If criteria are not met, the analytical system must be investigated, the fault diagnosed and corrected, and system suitability must be re-run successfully before proceeding [21]. This ensures the integrity and reliability of all generated analytical data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of spectroscopic methods under USP and EP standards requires the use of specific, high-quality reagents and materials. The following table details key items essential for regulatory compliance.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Spectroscopic Analysis

| Item | Function & Application | Regulatory Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| USP/EP Reference Standards | Highly purified, characterized substances used to calibrate instruments, validate methods, and identify and quantify analytes [24] [21]. | Must be obtained from authorized sources (e.g., USP, EDQM). Their use is mandatory for compendial methods to ensure data acceptance by regulators. |

| Deuterated NMR Solvents | High-purity solvents (e.g., D₂O, CDCl₃, DMSO-d₆) used for NMR sample preparation to provide a lock signal and avoid interference with sample proton signals [20]. | Must be of high isotopic and chemical purity to prevent extraneous peaks and ensure accurate quantitative results, as required for impurity profiling. |

| Spectroscopic-Grade Solvents | High-purity solvents with low UV absorbance and minimal fluorescent impurities, used for UV-Vis and fluorescence spectroscopy [20]. | Essential for achieving low baseline noise and accurate quantification, directly impacting method accuracy and LOD/LOQ as per ICH Q2(R2). |

| ATR Crystals (for IR) | Durable crystals (e.g., diamond, ZnSe) used in Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) accessories for minimal sample preparation IR analysis [20]. | The crystal material must be chemically compatible with the sample. A clean, undamaged crystal is critical for obtaining reproducible spectral fingerprints for identity testing. |

| Certified Cuvettes and Cells | Precision optical cells with certified pathlengths and transmission characteristics for UV-Vis and IR spectroscopy [20]. | Proper alignment and cleanliness are required for accurate and reproducible absorbance measurements, affecting the precision and accuracy of the analytical method. |

The regulatory landscape for pharmaceutical analysis, particularly for spectroscopic methods, is defined by a hierarchy of complementary guidelines. The ICH Q2(R2) guideline provides the overarching international framework for analytical validation [18]. Regulatory authorities like the FDA enforce compliance with these standards [18], while pharmacopoeias such as USP and EP provide the detailed, practical testing procedures and acceptance criteria [19] [21]. For scientists, success in this environment depends on a dual understanding: first, mastering the core scientific principles of techniques like UV-Vis, IR, and NMR spectroscopy, and second, rigorously applying the documented requirements for method validation, system suitability, and quality control as stipulated by the relevant regulatory and compendial bodies. As these standards continue to evolve—exemplified by the recent ICH Q2(R2) update and the EP's move to an online-only format in 2025 [18] [25]—a proactive approach to monitoring and implementing new guidance is essential for maintaining compliance and ensuring the continuous quality, safety, and efficacy of pharmaceutical products.

Understanding Selectivity vs. Specificity in Spectroscopic Techniques

In the field of spectroscopic analytical methods, the terms selectivity and specificity describe a method's ability to accurately identify and quantify an analyte. While often used interchangeably in informal settings, a critical distinction exists between them from a method validation perspective. Specificity refers to the ability to assess the analyte unequivocally in the presence of other components that are expected to be present, such as impurities, degradation products, or matrix components [26] [10]. It ensures that the measured signal is due to a single component only [10]. Selectivity, on the other hand, describes the ability of the method to differentiate and quantify multiple different analytes within the same mixture [27]. A highly specific method is one that responds to only one analyte, whereas a selective method can respond to several different analytes independently and without interference [26].

Understanding this distinction is paramount for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals when developing and validating analytical methods, as it directly impacts the reliability, accuracy, and regulatory acceptance of the data generated.

Conceptual Distinction: The Key Analogy

A commonly used analogy to distinguish these two concepts involves a lock and key.

- Specificity is akin to having a single key that opens only one specific lock. The method is designed to identify and interact with one target analyte, much like a key fits only one lock. Using this method, you can confidently identify that one correct key (analyte) from a bunch of keys (a complex sample), without needing to identify all the other keys present [26] [27].

- Selectivity, in contrast, is like having a master key chain that can open several different locks. The method is tuned to recognize, differentiate, and measure several distinct analytes within the same sample. It requires the identification of all target components in the mixture, not just one [26] [27].

The relationship between these concepts can be visualized as a spectrum. A method that is perfectly specific for a single analyte sits at one end, while a method that is highly selective and can resolve many analytes sits at the other. In this context, specificity can be considered the ultimate degree of selectivity [28].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between an analytical method, its interaction with a sample, and the resulting outcomes that define it as selective or specific.

Experimental Protocols for Demonstration

Demonstrating Specificity in UV-Spectroscopy

A validated UV-spectrophotometric method for the estimation of terbinafine hydrochloride provides a clear protocol for demonstrating specificity [29].

- Preparation of Standard Solution: Accurately weigh 10 mg of the pure drug substance (analyte) and dissolve in distilled water in a 100 ml volumetric flask to make a standard stock solution of 100 µg/ml.

- Sample Solution with Matrix: To assess potential interference from a sample matrix, a pharmaceutical formulation (e.g., an eye drop solution) is processed. For example, 5 ml of the formulation is diluted to 100 ml with distilled water. A portion of this solution is further diluted to a working concentration.

- Analysis and Comparison: Both the standard solution and the sample solution are scanned in the UV range of 200–400 nm. The spectrum of the sample solution is overlaid with that of the standard.

- Acceptance Criterion: Specificity is demonstrated if the analyte in the sample solution shows the same absorbance maximum (λmax, e.g., 283 nm for terbinafine) as the standard, and there are no additional peaks or significant shifts in the baseline caused by the formulation excipients, confirming no interference [29].

Demonstrating Selectivity in Chromatography

While not a spectroscopic technique, the principles of demonstrating selectivity in chromatography are well-defined and can be conceptually applied to multi-analyte spectroscopic methods like diode-array detection.

- Preparation of Mixed Standard: A solution containing all target analytes is prepared at a specified concentration.

- Forced Degradation/Impurity Spiking: The sample (drug substance or product) is subjected to stress conditions (e.g., heat, light, acid, base, oxidation) to generate degradation products. Alternatively, known impurities are added to the sample.

- Chromatographic Analysis: The mixed standard and the stressed/ spiked sample are analyzed using the chromatographic method.

- Acceptance Criterion: Selectivity is demonstrated by the baseline resolution (typically resolution, Rs > 2.0) between all analyte peaks and the closest eluting potential interferent (degradation product, impurity, or excipient). Peak purity tests using Photodiode-Array (PDA) or Mass Spectrometry (MS) detectors are employed to confirm that each peak is attributable to a single component [10].

Comparative Data and Validation Parameters

The validation of an analytical method involves checking several performance characteristics. The table below summarizes how selectivity and specificity fit among other key parameters, using examples from validation studies [29] [10].

Table 1: Key Analytical Validation Parameters and Examples

| Validation Parameter | Definition | Typical Experimental Data & Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Closeness of agreement between a measured value and an accepted reference value [30] [10]. | % Recovery of known, added amount. Example: 98.54% - 99.98% recovery at 80%, 100%, 120% levels [29]. |

| Precision | Closeness of agreement among individual test results from repeated analyses. Expressed as %RSD [30] [10]. | Intra-day %RSD < 2% for concentrations 10-20 µg/ml [29]. |

| Specificity | Ability to assess the analyte unequivocally in the presence of potential interferents [26] [10]. | No interference from sample matrix observed at the analyte's λmax; peak purity test passes [29] [10]. |

| Selectivity | Ability to differentiate and measure multiple analytes in a mixture [26] [27]. | Resolution (Rs) between critical analyte pair > 2.0; all target analytes are individually identified and quantified [10]. |

| Linearity | Ability to obtain results directly proportional to analyte concentration [10]. | Correlation coefficient (r²) > 0.999 over a specified range (e.g., 5-30 µg/ml) [29]. |

| LOD/LOQ | Lowest concentration that can be detected (LOD) or quantified (LOQ) with acceptable precision and accuracy [10]. | LOD: S/N ≈ 3:1. LOQ: S/N ≈ 10:1. Example: LOD = 0.42 µg, LOQ = 1.30 µg [29]. |

| Robustness | Measure of a method's capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters [10]. | Method performance remains within specified limits when parameters (e.g., pH, temperature) are slightly altered. |

Another critical aspect is the application of these parameters across different types of analytical procedures, as required by regulatory guidelines like ICH Q2(R1).

Table 2: Requirement of Specificity/Selectivity for Different Types of Analytical Procedures

| Type of Analytical Procedure | Requirement for Specificity/Selectivity |

|---|---|

| Identification Tests | Specificity is absolutely necessary. Must ensure the method can discriminate between the analyte and closely related substances. Typically confirmed by comparing to a known reference standard [26] [10]. |

| Impurity Tests (Quantification) | Selectivity is critical. Must demonstrate that the analyte (drug) is resolved from all potential impurities and degradation products. This is often proven via forced degradation studies [10]. |

| Assay (Content/Potency) | High selectivity is required. Must be able to quantify the analyte accurately in the presence of excipients, impurities, etc. Lack of interference must be demonstrated [26] [10]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials and reagents commonly required for validating the selectivity and specificity of an analytical method, based on the protocols cited.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Validation Studies

| Item | Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Analyte Reference Standard | Serves as the primary benchmark for identifying the target analyte(s), establishing the calibration curve, and confirming specificity against the sample matrix [29]. |

| Pharmaceutical Formulation (Placebo & Medicated) | The placebo (containing all excipients) is used to check for matrix interference. The medicated product is the actual test sample for the analysis [29]. |

| Known Impurities/Degradation Products | When available, these are used to spike the sample and critically challenge the method's selectivity by proving resolution from the main analyte [10]. |

| Appropriate Solvents (e.g., Distilled Water, HPLC-grade Methanol) | Used for the preparation of standard and sample solutions. The solvent must not interfere with the analyte signal at the wavelengths or conditions used [29]. |

| Acids, Bases, Oxidizing Agents (e.g., HCl, NaOH, H₂O₂) | Used in forced degradation studies to intentionally stress the sample and generate degradation products, providing a rigorous test for the method's selectivity [10]. |

| Buffer Salts and Reagents | Used to prepare mobile phases (in chromatography) or to control pH in spectroscopic assays, which can be critical for analyte stability and spectral profile [10]. |

Regulatory and Practical Implications

From a regulatory standpoint, the ICH Q2(R1) guideline explicitly defines and requires specificity for the validation of identification, impurity, and assay tests [26] [10]. While the term "selectivity" is not used in this primary guideline, it is present in other contexts, such as the European guideline on bioanalytical method validation [26]. This has led to a preference for "specificity" in pharmacopeial and quality control laboratory contexts, whereas "selectivity" is often favored in other branches of analytical chemistry and bioanalysis [28] [26].

In practice, for spectroscopic techniques, proving a method is truly specific (responding to only one analyte in a complex matrix) can be challenging. Techniques like derivative spectroscopy or the use of diode-array detectors for peak purity assessment are often employed to enhance selectivity and provide stronger evidence for specificity [10]. The ultimate goal is to ensure that the method is fit-for-purpose, providing reliable and unambiguous data for decision-making in drug development.

The Importance of Robustness and Ruggedness in Method Development

In the field of analytical chemistry, particularly for spectroscopic and chromatographic methods in pharmaceutical development, the reliability of an analytical procedure is paramount. The consistency of results impacts critical decisions from patient diagnoses to product safety determinations [31]. Among the various validation parameters, robustness and ruggedness stand as crucial, yet often misunderstood, safeguards that ensure analytical methods produce reliable data not just under ideal conditions, but amidst the inevitable variations of real-world laboratory environments [32] [31]. While these terms are sometimes used interchangeably, they represent distinct concepts that together provide a comprehensive picture of a method's reliability [33]. This guide explores the importance of both parameters, providing experimental protocols, comparative data, and practical tools to strengthen analytical method development.

Defining Robustness and Ruggedness

Robustness refers to the capacity of an analytical method to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters, providing an indication of its reliability during normal usage [34] [33]. It represents the method's stability when subjected to intentional, minor changes in internal parameters such as mobile phase pH, temperature, or flow rate in chromatographic methods [32] [35].

Ruggedness, meanwhile, evaluates the degree of reproducibility of test results obtained when the same method is applied under a variety of normal test conditions, such as different laboratories, analysts, instruments, or days [33]. It measures the method's resistance to external factors that may vary between different testing scenarios [32].

Key Distinctions

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between Robustness and Ruggedness

| Aspect | Robustness | Ruggedness |

|---|---|---|

| Focus | Small variations in method parameters | Larger variations in conditions, including operator and equipment [32] |

| Type of Variations | Minor, deliberate changes (e.g., temperature, pH, flow rate) [32] | Broader, environmental factors (e.g., different analysts, instruments, labs) [32] [31] |

| Objective | Test method reliability under slight condition changes [32] | Test method consistency across different settings and operators [32] |

| Scope | Narrow: focuses on conditions directly affecting analysis [32] | Broad: focuses on reproducibility across environments and users [32] |

| Testing Environment | Typically intra-laboratory [31] | Often inter-laboratory [31] |

| Primary Application | Identifying critical method parameters requiring control [34] | Establishing method transferability between sites [31] |

Experimental Protocols for Assessment

Robustness Testing Methodology

Robustness testing should be performed during the method development phase to identify parameters that require strict control [34] [33]. A systematic approach involves:

Factor Selection: Identify operational and environmental factors from the method description. For a chromatographic method, this typically includes mobile phase pH, composition, flow rate, column temperature, and detection wavelength [34] [33].

Level Definition: Define high and low values for each factor that slightly exceed expected normal variations. For example, a nominal flow rate of 1.0 mL/min might be tested at 0.9 mL/min and 1.1 mL/min [34].

Experimental Design Selection: Utilize multivariate screening designs to efficiently evaluate multiple factors simultaneously. Common approaches include full factorial, fractional factorial, or Plackett-Burman designs [34] [33]. These designs allow for the evaluation of numerous factors with a minimal number of experimental runs.

Response Measurement: Execute experiments and measure critical responses such as peak area, retention time, resolution, tailing factor, and theoretical plate count [34].

Data Analysis: Calculate effects for each factor and identify statistically significant impacts on method responses. Statistical analysis helps distinguish meaningful effects from normal variation [34].

System Suitability Limits: Based on the results, establish scientifically justified system suitability parameters to ensure method validity during routine use [34].

Ruggedness Testing Methodology

Ruggedness testing evaluates the method's performance under realistic variations that occur between different testing environments:

Inter-Analyst Variation: Different analysts with varying skill levels and experience execute the identical method using the same instrument and reagents [32] [33].

Inter-Instrument Variation: The method is performed on different instruments of the same model, or different models with similar specifications, within the same laboratory [32] [31].

Inter-Laboratory Variation: The method is transferred to and executed in different laboratories, often as part of collaborative studies [33] [31].

Day-to-Day Variation: Analyses are conducted on different days to account for potential environmental fluctuations and reagent variations [33].

Data Analysis: Results from all variations are statistically compared using appropriate tests (e.g., ANOVA) to determine if observed differences are statistically significant [33].

Comparative Experimental Data

Case Study: HPLC Method Development

A developed and validated RP-HPLC method for simultaneous quantification of Exemestane and Thymoquinone exemplifies robust method development. The study employed a Box-Behnken design (BBD) for optimization, considering three independent variables (% acetonitrile, flow rate, and injection volume) and multiple dependent responses (retention times, tailing factors, and theoretical plates) [36].

Table 2: Robustness Testing Results for an RP-HPLC Method

| Factor Tested | Variation Range | Impact on Retention Time | Impact on Peak Area | Significance Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Acetonitrile | 50-70% | Significant change observed [36] | Controlled variation | Critical parameter [36] |

| Flow Rate | 0.6-1.0 mL/min | Significant change observed [36] | Controlled variation | Critical parameter [36] |

| Injection Volume | 15-25 μL | Minimal change | Minimal change | Non-critical parameter [36] |

| Column Temperature | ±2°C | Moderate change | Minimal change | Controlled parameter [32] |

| Mobile Phase pH | ±0.1 units | Significant change possible [32] | Minimal change | Critical for ionizable compounds [32] |

Ruggedness Assessment Data

Ruggedness testing data from a study on mass spectral data comparison for seized drug identification demonstrates the practical importance of this parameter:

Table 3: Ruggedness Testing Across Different Conditions

| Variation Factor | Test Conditions | Resulting Impact | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Different Analysts | Multiple trained analysts | Minimal impact on results when method is well-documented [32] | Not significant (p > 0.05) [32] |

| Different Instruments | Various GC-MS models | Significant effects observed, requiring calibration adjustment [37] | Significant (p < 0.05) [37] |

| Different Laboratories | Multiple operational forensic labs | Notable variations requiring method refinement [37] | Significant (p < 0.05) [37] |

| Reagent Lots | Different batches from suppliers | Minor variations observed [32] | Not significant (p > 0.05) [32] |

| Day-to-Day | Analyses conducted over two weeks | Controlled variations within acceptable limits [33] | Not significant (p > 0.05) [33] ``` |

Visualizing Experimental Workflows

Robustness Testing Protocol

Ruggedness Testing Protocol

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Materials

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for Robustness/Ruggedness Studies

| Material/Reagent | Function in Assessment | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| HPLC-grade solvents | Mobile phase components with controlled purity | Test variations in composition and supplier [36] |

| Reference standards | System qualification and response measurement | Assess detector stability and retention reproducibility [36] |

| Different column lots | Stationary phase variability assessment | Evaluate retention time stability across manufacturing batches [32] [33] |

| Buffer solutions | pH control in mobile phase | Test method sensitivity to slight pH variations [32] |

| Multiple instrument models | Ruggedness testing across platforms | Verify method transferability between equipment [31] [37] |

| Chemometric software | Experimental design and data analysis | Enable multivariate analysis of robustness factors [34] [36] |

Robustness and ruggedness represent complementary pillars of reliable analytical method development. While robustness focuses on a method's internal stability against minor parameter fluctuations, ruggedness addresses its external reproducibility across different operators, instruments, and environments [32] [31]. The experimental data and protocols presented demonstrate that systematic evaluation of both parameters is not merely a regulatory formality, but a strategic investment in method quality and transferability [31]. Incorporating robustness testing early in method development identifies critical parameters requiring control, while rigorous ruggedness assessment ensures methods will perform consistently when transferred to other laboratories or implemented in routine use [34] [33]. For spectroscopic and chromatographic methods in pharmaceutical analysis, this comprehensive approach provides the documented evidence necessary to ensure analytical procedures remain fit-for-purpose throughout their lifecycle, ultimately safeguarding product quality and patient safety.

Implementing Validation Protocols for FT-IR, Raman, and UV-Vis Spectroscopy

Validation of analytical methods is a critical process that ensures spectroscopic and chromatographic data are reliable, accurate, and reproducible for scientific and regulatory decision-making. The process experimentally demonstrates that an analytical method is suitable for its intended purpose by assessing key performance characteristics. While core validation parameters share common principles across techniques, their specific implementation, acceptance criteria, and methodological approaches differ significantly based on the underlying technology and measurement principles. This guide provides a detailed comparison of validation practices for four prominent analytical techniques: Fourier-Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy, Ultraviolet-Visible-Near-Infrared (UV-Vis-NIR) spectroscopy, and Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Understanding these technique-specific considerations enables researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to select appropriate validation strategies that meet both scientific rigor and regulatory standards.

The table below summarizes the core validation parameters and their technique-specific considerations across FT-IR, Raman, UV-Vis-NIR, and LC-MS/MS.

Table 1: Technique-Specific Validation Parameters Across Analytical Methods

| Validation Parameter | FT-IR Spectroscopy | Raman Spectroscopy | UV-Vis-NIR Spectroscopy | LC-MS/MS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Validation Focus | Instrument performance verification [38] | Model predictive accuracy & clinical utility [39] | Non-destructive quantitative analysis [40] [41] | Accurate quantification in complex matrices [42] [43] |

| Accuracy Assessment | Verification against known standards (e.g., polystyrene) [38] | Classification accuracy in blinded test sets (e.g., 91.3% for cervical precancer) [39] | Comparison with reference methods (e.g., refractometer) [40] | Comparison of measured vs. true value of analyte; spike/recovery experiments [43] |

| Precision/Reproducibility | Wavenumber & transmittance reproducibility checks [38] | Spectral reproducibility & model precision [39] | Repeatability of spectral measurements & prediction models [40] | Agreement between multiple measurements of same sample [43] |

| Specificity/Selectivity | Resolution of absorbance peaks (e.g., using ammonia gas) [38] | Ability to detect biochemical changes in complex matrices [39] | Specificity for target analytes amidst interferents [41] | Measurement of target analyte in presence of other components [43] |

| Linearity | Inspection of absorbance vs. concentration linearity [38] | Linear response for quantitative models (e.g., PLSR) [40] | Producing results proportional to analyte concentration [41] [43] | Response proportional to analyte concentration over defined range [43] |

| Key Quantitative Metrics | 100% & 0% transmittance, wavenumber accuracy [38] | Root Mean Square Error of Prediction (RMSEP), classification accuracy [39] [44] | Coefficient of Determination (R²p), RMSEP [40] | Accuracy, precision, matrix effect, recovery [43] |

| Detection/Quantification Limits | Not typically a primary focus for hardware validation [38] | Lowest detectable biochemical change in samples [39] | Lowest quantifiable concentration with specified confidence [5] | Lower Limit of Quantification (LLOQ), signal-to-noise ratio (e.g., 20:1) [42] [43] |

| Regulatory/Standard Guides | JIS K0117, ASTM E1421, Japanese/European Pharmacopoeia [38] | ICH Q2(R1), FDA guidelines, SFSTP validation strategy [44] | Standard chemometric validation (e.g., PLSR, RMSEP) [40] | ICH Q2(R1), FDA guidelines, CLSI C62-A [42] [43] |

Technique-Specific Experimental Protocols

FT-IR Spectroscopy Validation

FT-IR validation primarily focuses on ensuring the instrument itself is operating within specified parameters, as outlined in various pharmacopeial and industrial standards [38].

Key Experimental Protocols:

- Wavenumber Accuracy: Measure the peak wavenumber positions of a well-characterized standard (e.g., polystyrene film, atmospheric CO₂, or ammonia gas) and calculate the difference from the accepted reference values [38].

- 0% and 100% Transmittance Line Tests: To investigate stray light and system response, measure a completely opaque sample for the 0%T line and perform an ambient air background measurement for the 100%T line [38].

- Resolution Check: Use a gas cell containing ammonia or carbon dioxide and verify that the instrument can resolve specific, closely spaced rotational-vibrational lines in the spectrum [38].

- Reproducibility: Measure a stable sample (e.g., polystyrene film) multiple times in a short period and confirm that the variation in both wavenumber and transmittance values falls within a pre-defined range [38].

Raman Spectroscopy Validation

Raman spectroscopy validation often centers on confirming the accuracy of quantitative models, especially when used for clinical diagnostics or process monitoring.

Key Experimental Protocols:

- Blinded Independent Test Set Validation: A classification model is developed using a training set of spectra (e.g., n=662 cervical cell samples). Its performance is then validated by applying the model to a completely separate, blinded set of samples (e.g., n=69) and calculating the classification accuracy [39].

- Validation for Quantitative Analysis (e.g., API Content): Following ICH/FDA guidelines, this involves assessing accuracy, precision, specificity, linearity, and range. A robust approach like the SFSTP's "total error" (bias + standard deviation) strategy using accuracy profiles can be employed to guarantee future measurement reliability [44].

- Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR) Modeling: For quantitative applications like SSC determination in fruit, a PLSR model is constructed from training data. The optimal number of PLS factors is determined via cross-validation, avoiding overfitting, and model performance is reported with metrics like R²p and RMSEP [40].

UV-Vis-NIR Spectroscopy Validation

Validation for UV-Vis-NIR techniques emphasizes non-destructive quantitative analysis and requires rigorous chemometric model validation.

Key Experimental Protocols:

- Soluble Solids Content (SSC) Estimation Model: For fruit quality analysis, spectra are collected from multiple points on each sample. After second derivative preprocessing using the Savitzky-Golay algorithm, a PLSR model is built to predict SSC (e.g., in Brix units). Model accuracy is reported with R²p and RMSEP [40].

- Agreement with Reference Methods: To validate a new NIR method for tablet assay, results are statistically compared to those from a established conventional method, such as UV-Vis spectrophotometry, to demonstrate parity or superiority [41].

- Mixing Kinetics Monitoring: The "conformity test" can be used to monitor powder blending. NIR spectra of the final blend are used to create a confidence band. Spectra acquired during subsequent mixing processes are tested for deviation within these set limits to determine homogeneity [41].

LC-MS/MS Validation

LC-MS/MS validation is a comprehensive process defined by strict regulatory guidelines to ensure reliable quantification of analytes in complex biological matrices.

Key Experimental Protocols:

- Calibration and Analytical Measurement Range (AMR): A full calibration curve (at least 5 non-zero, matrix-matched calibrators) is established to define the AMR. The Lower and Upper Limits of Quantification (LLOQ/ULOQ) are verified, with predefined pass criteria for signal-to-noise at LLOQ and for back-calculated calibrator concentrations (typically ±15-20%) [42] [43].

- Accuracy and Precision: Assessed by analyzing quality control (QC) samples at multiple concentrations (low, medium, high) in replicates across different runs. Accuracy (mean measured concentration vs. true value) and Precision (degree of scatter in the results) must meet pre-defined criteria (e.g., ±15%) [43].

- Specificity and Matrix Effects: Specificity is proven by demonstrating no interference from other components in the sample. Matrix effect is evaluated by extracting and analyzing multiple individual lots of the blank matrix spiked with the analyte. The precision and accuracy of the back-calculated concentrations across these different lots confirm whether ion suppression/enhancement is under control [43].

- Stability Experiments: Analyte stability is assessed under various conditions (e.g., benchtop, in-autosampler, freeze-thaw cycles, long-term storage) by comparing the measured concentration of stability samples against freshly prepared standards [43].

Visualization of Analytical Method Validation Workflows

LC-MS/MS Series Validation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the sequential decision-making process for validating an analytical series in LC-MS/MS, which ensures the reliability of each batch of patient samples.

Spectroscopic Model Development & Validation Workflow

This diagram outlines the generalized workflow for developing and validating quantitative or classificatory models in spectroscopic techniques like Raman and NIR.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Successful method validation requires careful selection and consistent use of high-quality materials and reagents. The following table details key items used in the experiments cited within this guide.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Analytical Validation

| Item Name | Function in Validation | Example Application/Justification |

|---|---|---|

| Polystyrene Film | A standard reference material for verifying wavenumber accuracy and resolution in FT-IR [38]. | Provides a stable, well-characterized spectrum with sharp peaks for instrument calibration and performance qualification [38]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) / Calibrators | Matrix-matched materials with known analyte concentrations used to establish the calibration curve and define the analytical measurement range [42]. | Essential for demonstrating linearity and accuracy in LC-MS/MS and spectroscopic quantitation; traceability to primary standards is critical [42] [43]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Samples | Samples spiked with known concentrations of the analyte at various levels (low, mid, high) to assess the precision and accuracy of each analytical run [43]. | Used in LC-MS/MS and quantitative spectroscopic methods to monitor run-to-run performance and ensure data integrity [43]. |

| ThinPrep Cervical Cytology Samples | A real-world clinical matrix used to develop and validate Raman spectroscopic models for disease classification [39]. | Provides a biologically relevant sample system to test the clinical utility and robustness of the spectroscopic method in a complex matrix [39]. |

| Metoprolol Tartrate (API) & Eudragit Polymer | Model Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) and excipient for validating in-line Raman methods in pharmaceutical manufacturing [44]. | Represents a typical drug-polymer system for hot-melt extrusion, allowing validation of API quantification in a process-relevant matrix [44]. |

| Ag-Cu Alloy Standards | Well-characterized, homogeneous materials with known composition for validating spectroscopic method accuracy and determining detection limits [5]. | Used in XRF spectroscopy to evaluate method performance in complex matrices and study the impact of composition on detection capabilities [5]. |

The validation of analytical methods is a foundational activity that ensures data quality and regulatory compliance, but its execution is highly technique-specific. FT-IR validation prioritizes instrumental performance against standardized criteria. Raman and UV-Vis-NIR spectroscopy often rely on robust chemometric models, validated with independent test sets and stringent statistical metrics. LC-MS/MS requires a comprehensive, protocol-driven approach to manage the complexities of chromatographic separation and mass spectrometric detection in biological matrices. Understanding these distinct frameworks allows researchers to implement validation strategies that are not only compliant with regulatory guidelines but also scientifically sound and fit-for-purpose, thereby ensuring the generation of reliable and meaningful analytical data.

Sample preparation is a critical foundation for accurate and reliable spectroscopic analysis. Inadequate preparation is a primary source of analytical error, accounting for as much as 60% of all spectroscopic inaccuracies [45]. The physical and chemical state of a sample directly influences its interaction with electromagnetic radiation, making proper preparation essential for valid results. This guide objectively compares preparation techniques for solids, liquids, and thin films, providing experimental protocols and data to inform method selection within spectroscopic method validation frameworks.

Solid Sample Preparation Techniques

Solid samples require extensive processing to achieve homogeneity and form factors suitable for spectroscopic analysis. Key techniques include grinding, milling, pelletizing, and fusion, each with distinct advantages for specific material types and analytical techniques like XRF, ICP-MS, and FT-IR [45].

Grinding and Milling

Grinding reduces particle size through mechanical friction, creating homogeneous samples essential for uniform radiation interaction. The choice of grinding equipment depends on material hardness, required particle size (typically <75μm for XRF), and contamination risks [45].

Milling offers superior control over particle size reduction and surface quality. It produces even, flat surfaces that minimize light scattering effects, provide consistent density across the sample surface, and expose internal material structure for more representative analysis [45].

Table 1: Comparison of Solid Sample Preparation Methods

| Technique | Best For | Final Particle Size | Key Equipment | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grinding | Tough samples (ceramics, ferrous metals) | Typically <75μm | Spectroscopic grinding machines, swing grinders | Minimizes heat formation, preserves chemistry | Potential for cross-contamination between samples |

| Milling | Non-ferrous materials (aluminum, copper alloys) | Controlled reduction | Programmable milling machines | Excellent surface quality, reduces scattering effects | Thermal degradation risk without cooling systems |

| Pelletizing | Powder analysis for XRF | N/A (powder transformed) | Hydraulic/pneumatic presses (10-30 tons), binders | Uniform density and surface properties, improved stability | Binder dilution factors must be accounted for |

| Fusion | Refractory materials (silicates, minerals, ceramics) | Complete dissolution | High-temperature furnaces (950-1200°C), platinum crucibles | Eliminates mineral/particle effects, unparalleled accuracy | Higher cost, more complex procedure |

Pelletizing and Fusion

Pelletizing transforms powdered samples into solid disks with uniform density and surface properties essential for quantitative XRF analysis. The process involves blending ground sample with a binder (wax or cellulose) and pressing at 10-30 tons to create stable pellets [45].

Fusion represents the most stringent preparation technique for complete dissolution of refractory materials into homogeneous glass disks. This method involves blending ground sample with flux (lithium tetraborate), melting at 950-1200°C in platinum crucibles, and casting as disks. Fusion prevents particle size and mineral effects that compromise other techniques [45].

Experimental Protocol: Modified QuEChERS for Soil Analysis

A recent study developed and compared three wide-scope sample preparation methods for determining organic micropollutants in soil using GC-HRMS: modified QuEChERS, Accelerated Solvent Extraction (ASE), and Ultrasonic Assisted Extraction (UAE) [46].

Methodology:

- Sample Processing: 5.00 g of freeze-dried soil sample used for all methods

- mQuEChERS Protocol: Added 5 mL water + 10 mL acetonitrile with shaking and ultrasonic bath

- Extraction: Supernatant collected with 4 g MgSO₄ + 1 g NaCl added

- Purification: Solvent change to 4 mL of 20% acetone in hexane, clean-up with Florisil cartridges

- Analysis: Final extracts evaporated under nitrogen, reconstituted in hexane, filtered to 200 μL

Performance Data: The modified QuEChERS method demonstrated recoveries of 70-120% for 75 analytes including pesticides, PAHs, PCBs, PCNs, and OCPs. Method precision was optimal with RSD < 11%, and limits of detection ranged from 0.04 to 2.77 μg kg⁻¹ d.w. [46]

Figure 1: Modified QuEChERS Workflow for Soil Samples

Liquid Sample Preparation Techniques

Liquid sample preparation focuses on dilution, filtration, and solvent selection to optimize analytical performance while minimizing matrix effects. These techniques are particularly crucial for sensitive analytical methods like ICP-MS, UV-Vis, and FT-IR [45].

Dilution and Filtration for ICP-MS