Water Contact Angle Measurement: A Quantitative Guide for Ensuring Optical Surface Cleanliness in Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on using Water Contact Angle (WCA) measurement as a quantitative, non-destructive method for verifying optical surface cleanliness.

Water Contact Angle Measurement: A Quantitative Guide for Ensuring Optical Surface Cleanliness in Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on using Water Contact Angle (WCA) measurement as a quantitative, non-destructive method for verifying optical surface cleanliness. It covers the foundational principles of wettability, detailing advanced methodological approaches from sessile drop to captive bubble techniques tailored for biomedical surfaces like endoscopes. The content addresses common troubleshooting challenges, including contamination sensitivity and environmental control, and offers a comparative analysis with other surface analysis techniques. By integrating validation strategies and real-world case studies, this resource empowers scientists to implement WCA as a reliable Key Performance Indicator (KPI) for process control, ultimately enhancing the reliability of critical optical components in clinical and research settings.

Water Contact Angle Fundamentals: The Science of Wettability and Surface Cleanliness

In the field of surface science, the contact angle is a fundamental quantitative measure that defines the wettability of a solid surface by a liquid. It is geometrically defined as the angle formed at the three-phase boundary where a liquid, gas, and solid intersect [1]. This measurement provides critical insights into the molecular-level interactions at a surface, making it an indispensable tool for research in optical surface cleanliness, where even microscopic contamination can disrupt performance. The value of the contact angle is a direct reflection of the balance between the surface tensions of the solid, liquid, and gas phases, as described by Young's equation [2] [1].

For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering contact angle measurement is crucial for characterizing material surfaces, validating cleaning processes, and ensuring the success of coatings and adhesives. This guide provides a comparative analysis of measurement methodologies, detailed experimental protocols, and an overview of the essential toolkit for reliable data acquisition.

Theoretical Foundation of Contact Angle

The theoretical foundation of contact angle measurement is rooted in the concept of surface free energy. A surface with high surface free energy (e.g., a clean metal) will cause a liquid droplet to spread out, resulting in a low contact angle and indicating hydrophilicity [2] [3]. Conversely, a surface with low surface free energy will cause the liquid to bead up, resulting in a high contact angle and indicating hydrophobicity [1] [4].

- Young's Model: This model describes the ideal equilibrium contact angle (θY) on a perfectly smooth, rigid, chemically homogeneous, and insoluble surface. It is defined by the balance of interfacial tensions: γSV = γSL + γLV cosθY, where γ represents the interfacial tensions between the solid (S), liquid (L), and vapor (V) phases [1] [5].

- Wenzel Model: On real, rough surfaces, the Wenzel state describes a scenario where the liquid droplet completely wets the surface texture. The model introduces a roughness factor (r) that amplifies the intrinsic wettability, making a hydrophilic surface more hydrophilic and a hydrophobic surface more hydrophobic [5].

- Cassie-Baxter Model: For surfaces where the liquid cannot penetrate the roughness, the Cassie-Baxter state occurs. The droplet rests on a composite surface of solid and trapped air, leading to exceptionally high contact angles, as seen in superhydrophobic phenomena [5].

Real-world surfaces, however, are rarely ideal. Factors like surface roughness and chemical heterogeneity mean that a droplet can reside in multiple metastable states, leading to a range of measurable contact angles rather than a single unique value [2] [1]. This reality necessitates the use of dynamic contact angle measurements to fully characterize a surface.

Figure 1: Theoretical models explaining contact angle behavior on different surface types.

Comparative Analysis of Measurement Techniques

Various methods exist for measuring contact angle, each with distinct advantages, limitations, and optimal application scenarios. The choice of technique depends on the required information, such as basic wettability screening or detailed analysis of surface heterogeneity.

Static vs. Dynamic Contact Angles

The two primary categories of measurements are static and dynamic.

- Static Contact Angle (Sessile Drop): This is the most common and simplest method. A single droplet is placed on the surface, and the contact angle is measured from an image. It is useful for initial wettability characterization and quality control [2] [1]. However, it provides limited information as the measured value can be any metastable state within the surface's energy landscape and is sensitive to evaporation and drop volume [2] [1].

- Dynamic Contact Angles: These measurements involve advancing and receding contact angles, which define the full range of possible angles on a real surface.

- Advancing Contact Angle (ACA) is the maximum stable angle measured by adding liquid to an existing droplet, causing the contact line to advance [1].

- Receding Contact Angle (RCA) is the minimum stable angle measured by removing liquid, causing the contact line to recede [1].

- Contact Angle Hysteresis is the difference between ACA and RCA (Hysteresis = ACA - RCA). A large hysteresis indicates high surface heterogeneity (roughness or chemical variation) and strong liquid adhesion to the surface [1].

Technique Comparison Table

Table 1: Comparison of primary contact angle measurement techniques.

| Technique | Measured Parameter | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Ideal for Surface Cleanliness Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Static Sessile Drop [2] [1] | Single contact angle value | Fast, simple, inexpensive, easy to automate for QC. | Only captures one metastable state; limited information on heterogeneity. | Quick verification of cleaning; hydrophilicity/phobicity classification. |

| Needle-in Dynamic Method [1] | Advancing (ACA) & Receding (RCA) Angles; Hysteresis. | Overcomes metastable states; reveals surface heterogeneity and adhesion. | More complex setup and analysis than static. | Detecting trace contamination on polymers [3]; assessing coating uniformity. |

| Wilhelmy Plate Method [1] | Advancing & Receding Angles averaged over sample perimeter. | Provides data over the entire sample immersion length; highly reproducible. | Requires uniform, flat sample with known perimeter; not for localized analysis. | Overall cleanliness assessment of well-defined substrates like glass slides or wafers. |

| Tilting Base Method [1] | Roll-off Angle and dynamic CA behavior. | Directly measures practical adhesion of droplets to a surface. | Specialized tilting stage required. | Evaluating self-cleaning surface efficacy. |

Advanced and Emerging Methodologies

Beyond traditional goniometry, advanced techniques are addressing its limitations and enhancing measurement capabilities.

- High-Resolution Optical Tensiometry: The accuracy of optical methods is highly dependent on image quality. High-resolution cameras (e.g., 5 MP) are critical as they minimize errors in baseline positioning. A one-pixel baseline shift can cause an error of up to 4° with a low-resolution camera but only 1° with a high-resolution system [6]. This is particularly important for hydrophobic surfaces where image distortion at the interface is more pronounced [6].

- Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) with Deep Learning: OCT is an emerging, non-contact technique that acquires high-resolution, three-dimensional tomographic images of droplets from the top, overcoming the profile-view limitation of goniometry [5]. When combined with deep learning models (e.g., ConvNeXt-Tiny with Bi-LSTM), it enables highly accurate (MAE = 1.14°), automated, and material-independent contact angle prediction, even on rough or curved surfaces where traditional goniometry struggles [5].

Experimental Protocols for Surface Cleanliness

A standardized experimental protocol is essential for obtaining reliable and reproducible contact angle data in surface cleanliness research.

Workflow for Standard Contact Angle Measurement

The following workflow, based on ASTM guidelines, outlines the key steps for a static sessile drop measurement [7].

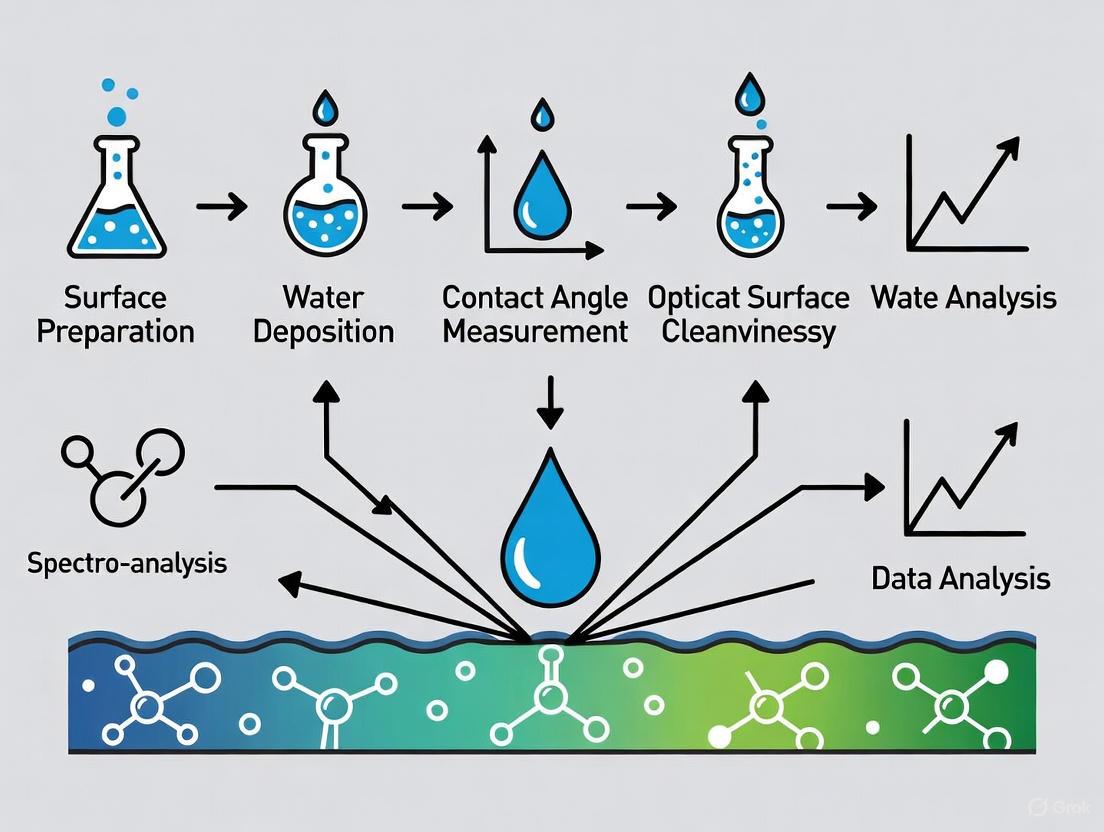

Figure 2: Standardized workflow for contact angle measurement per ASTM guidelines.

Step 1: Sample Preparation

- Cut the sample to manageable dimensions (e.g., 15mm wide strips) [7].

- Clean the surface with appropriate solvents (e.g., ethanol, isopropanol) using lint-free cloths to remove oils, fingerprints, and contaminants. Avoid touching the measurement area [7].

- For polymer films, remove static charges using an air ionizer to prevent erratic droplet behavior [7].

- Mount the sample on the goniometer stage, ensuring it is flat and level.

Step 2: Environmental Control

- Maintain the laboratory at a stable temperature of 23 ± 2°C and monitor relative humidity [7]. Fluctuations can alter liquid surface tension and affect droplet evaporation.

- Allow the sample and equipment to equilibrate to room temperature for at least 15 minutes before testing [7].

Step 3: Droplet Deposition

- Use a high-precision syringe system to dispense the probe liquid (typically high-purity deionized water). Ensure no air bubbles are present [7].

- The standard droplet volume is typically 5-8 µL, often specified as 6 µL [7].

- Position the needle 1-2 mm above the sample surface. Form a pendant droplet and gently bring the surface into contact with it before lowering the stage to deposit the droplet [7].

Step 4: Image Capture

- Capture the droplet image within 10-15 seconds of deposition to minimize evaporation effects [7].

- Ensure even, high-contrast lighting to create a sharp droplet profile with a well-defined baseline [7].

- Use a high-speed, high-resolution camera to ensure accurate edge detection [6].

Step 5: Image Analysis

- Use the instrument's software to automatically fit the droplet shape (e.g., using Young-Laplace or circle fitting algorithms) and calculate the contact angle [4].

- Manually verify that the software has correctly identified the droplet edges and the baseline (solid-liquid interface) [7].

Step 6: Data Reporting

- Perform at least 5-10 measurements at different locations on the sample surface to ensure statistical reliability [7].

- Report the individual contact angles, mean value, standard deviation, number of measurements, and all test conditions (temperature, humidity, droplet volume) as required by ASTM standards [7].

Data Interpretation for Cleanliness

- Metal Surfaces: A clean metal surface is highly energetic and hydrophilic, exhibiting a low water contact angle. Contamination (e.g., grease) drastically increases the contact angle. Effective cleaning (e.g., ultrasonic cleaning, plasma treatment) lowers the angle towards its intrinsic clean value [3].

- Polymer Surfaces: Interpretation can be less straightforward, as a clean polymer may inherently have a high contact angle. In these cases, dynamic contact angles are more informative. Contamination often significantly affects the receding contact angle, making it a more sensitive indicator of cleanliness than the static angle [3].

Table 2: Example contact angle data demonstrating the effect of cleaning on different materials.

| Material | Surface Condition | Static Water Contact Angle | Key Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Copper [3] | Contaminated (as received) | 69° | Hydrophilic, but contaminated. |

| After ultrasonic cleaning | 26° | Effective cleaning; surface is highly hydrophilic. | |

| Nickel [3] | Contaminated (as received) | 63° | Hydrophilic, but contaminated. |

| After ultrasonic cleaning | 22° | Effective cleaning; surface is highly hydrophilic. | |

| Polymer [3] | Contaminated | High RCA | Contamination pins the receding contact line. |

| After Cleaning | Low RCA | Clean surface allows the contact line to recede freely. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key equipment and reagents for contact angle experiments.

| Item | Function/Description | Critical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Optical Tensiometer [8] | The core instrument for measuring contact angle via droplet image analysis. | High-resolution camera (≥5 MP) [6], automated dispensing system, software with advanced fitting algorithms. |

| High-Precision Syringe [7] | Dispenses the probe liquid with precise volume control. | Calibrated for volumes in the µL range; capable of smooth, pulsed-free liquid delivery. |

| Probe Liquid (Di-water) [7] | The liquid placed on the surface to measure wettability. | High-purity deionized water with known surface tension (e.g., 72.8 ± 0.5 mN/m at 20°C). |

| Cleaning Solvents [7] | Used to prepare and clean sample surfaces before measurement. | High-purity solvents like isopropyl alcohol, acetone; used with lint-free wipes. |

| Anti-Static Gun [7] | Neutralizes static charge on insulating samples (e.g., polymers). | Prevents distorted droplet shapes due to electrostatic forces. |

| Environmental Chamber | Encloses the measurement area to control temperature and humidity. | Maintains stable conditions (e.g., 23°C) to prevent evaporation-driven angle changes. |

Contact angle measurement remains a cornerstone technique for the quantitative assessment of surface wettability and cleanliness. While static sessile drop measurements offer a rapid and accessible method for basic characterization, dynamic advancing and receding angles provide a deeper, more reliable understanding of surface heterogeneity and contamination. The ongoing integration of advanced technologies like optical coherence tomography and deep learning is pushing the boundaries of accuracy and automation, enabling researchers to tackle more complex surface challenges. For scientists in drug development and optical surface research, a rigorous, standardized approach to contact angle measurement—selecting the appropriate technique and meticulously controlling experimental conditions—is paramount for generating meaningful data that drives innovation and ensures product quality.

Water contact angle (WCA) analysis serves as a critical, non-destructive tool for probing surface chemistry and contamination states across research and industrial applications. This technique quantifies surface wettability, where lower angles (<90°) indicate hydrophilic, high-energy surfaces typical of clean metals or contaminants with polar groups, while higher angles (>90°) signify hydrophobic, low-energy surfaces characteristic of organic contamination or low-energy materials. Despite its simplicity, WCA measurement provides exceptional sensitivity to molecular-level surface changes, enabling researchers to detect monolayer contamination, verify cleaning efficacy, and monitor surface aging. This guide examines the experimental parameters, comparative methodologies, and practical applications of WCA analysis for surface cleanliness research, providing detailed protocols and data interpretation frameworks for scientific and industrial contexts.

The Fundamental Relationship Between WCA and Surface State

Water contact angle measurement functions as a first-line diagnostic tool in surface science because it directly reflects the intermolecular forces at the solid-air interface. The underlying principle states that surfaces with high surface free energy (SFE)—typically clean metals, ceramics, and materials with polar functional groups—readily spread water droplets, resulting in low WCAs [3] [9]. Conversely, surfaces with low SFE—such as those contaminated with hydrocarbons, silicones, or comprised of non-polar polymers—resist wetting, producing high WCAs [10] [3].

The correlation between WCA and surface cleanliness is particularly pronounced on metal surfaces. Theoretically, clean metal surfaces possess extremely high surface free energy (even exceeding 1000 mN/m), but in practice, they immediately react with airborne molecules, forming a contamination layer that dramatically alters wettability [3]. Studies demonstrate that hydrocarbon adsorption can increase WCAs on flat copper samples from approximately 45° to 100° [11]. This sensitivity makes WCA an excellent indicator for verifying cleaning procedures before critical processes like coating, bonding, or painting [10] [3].

For polymer surfaces, interpretation requires greater nuance. While a contaminated surface often shows an elevated WCA, some clean polymers inherently exhibit high angles (e.g., Teflon at ~120°) [3]. In these cases, advancing and receding contact angle measurements provide more reliable cleanliness assessment, as the difference between them (contact angle hysteresis) often reveals contamination not apparent in static measurements [3].

Comparative Data: How Contamination and Materials Affect WCA

The following tables synthesize experimental WCA data from various studies, demonstrating how different contamination states and material chemistries influence measured wettability.

Table 1: WCA Changes on Metal Surfaces After Sequential Cleaning Steps [3]

| Surface Material | Initial WCA (Contaminated) | After Ultrasonic Soap Cleaning | After Additional Cleaning | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copper | 70° | 50° | <10° | Additional cleaning via plasma or chemical treatment |

| Nickel | 60° | 40° | <10° | Additional cleaning via plasma or chemical treatment |

Table 2: WCA Variation Due to Measurement and Environmental Factors [11]

| Factor | Condition Variation | Impact on Static WCA | Recommended Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Storage | Ambient air vs. controlled environment | Differences up to 60% | Store samples in inert atmosphere or clean containers |

| Droplet Evaporation | 0 vs. 10 minutes in dry air | Reduction of 30-50% | Measure within seconds of droplet placement |

| Droplet Volume | 3 µL vs. 10 µL | Significant variation | Standardize volume (typically 3-5 µL) |

| Water Grade | Different purity levels | Measurable differences | Use high-purity water (e.g., HPLC grade) |

Table 3: Classification of Surface Wettability by Water Contact Angle [9]

| WCA Range | Wettability Classification | Typical Surface Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| ~0° - 10° | Super-hydrophilic | Immediate spreading, high-energy surfaces |

| 10° - 90° | Hydrophilic | Good wettability, clean metals, polar groups |

| 90° - 150° | Hydrophobic | Poor wettability, hydrocarbon contamination, low-energy polymers |

| >150° | Super-hydrophobic | Extreme water beading, micro-structured surfaces |

Experimental Protocols for Reliable WCA Measurements

Standard Sessile Drop Method

Principle: A water droplet is dispensed onto a surface, and the angle at the three-phase contact line (solid-liquid-vapor) is measured optically [11] [9].

Detailed Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Clean samples in ethanol using an ultrasonic bath for 3 minutes. Dry with a stream of clean, oil-free air to prevent re-contamination [11].

- Environmental Control: Conduct measurements at stable room temperature (e.g., 22°C) and humidity. Note that low relative humidity (~20%) accelerates evaporation, significantly reducing WCA within minutes [11].

- Droplet Application: Use an automated dispensing system with a Hamilton syringe (e.g., 100 µL). Standardize droplet volume (3-5 µL) and dosing speed (e.g., 2.5 µL/s) for consistency [11].

- Image Capture & Analysis: Capture high-resolution images within 5 seconds of droplet application. Use an elliptical fit method for angles between 10° and 120°. Measure both sides of the droplet and average multiple images (e.g., 3) per droplet [11].

Captive Bubble Method for Hydrophilic Surfaces

Principle: An air bubble is injected beneath a material submerged in water, and the contact angle is measured at the bubble interface [12]. This method is particularly advantageous for hydrophilic, flexible, or fragile surfaces (e.g., free-standing graphene) where sessile drops may spread uncontrollably or damage the sample.

Detailed Protocol:

- Setup: Submerge the sample in a chamber of high-purity water. Use an inverted micro-syringe with a bent needle positioned close to the sample surface.

- Bubble Formation: Gently inject an air bubble (volume 0.2-6 µL) until it contacts the submerged surface.

- Angle Measurement: Capture images of the bubble profile. For flexible materials, account for substrate inflection by measuring angles above (θabove) and below (θbelow) the contact line. Calculate the water contact angle as: 180° − (θabove + θbelow) [12].

- Validation: This method yields equivalent results to the sessile drop technique on standard materials (e.g., 60° on HOPG) while protecting clean surfaces from airborne contamination [12].

Diagram: Water Contact Angle Measurement Workflow. Two primary methods, Sessile Drop and Captive Bubble, are selected based on surface properties.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for WCA Measurements

| Item | Function & Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Water | Primary measurement liquid for sessile drop | HPLC grade or equivalent; low conductivity [11] |

| Ethanol (Analytical Grade) | Sample cleaning and degreasing | 99.8% purity for ultrasonic cleaning [11] |

| Hamilton Syringe | Precise droplet dispensing | 100 µL capacity; stainless steel needle [11] |

| Contact Angle Goniometer | Optical measurement system | Automated droplet dispensing & image analysis [10] [9] |

| Plasma Cleaner | Surface activation & contamination removal | Oxygen or argon plasma for ultimate cleanliness [3] |

| Environmental Chamber | Control of humidity and temperature | Prevents evaporation artifacts during measurement [11] |

Critical Limitations and Complementary Techniques

While WCA provides exceptional sensitivity to surface chemistry changes, researchers must recognize its limitations. WCA measurements cannot detect subsurface contamination that might affect bond performance, and surface roughness or curvature can introduce measurement variability if not properly accounted for [10]. Furthermore, WCA alone is not a reliable predictor of complex biological responses like cellular attachment. Studies using diverse material libraries have failed to find consistent relationships between WCA and microbial or stem cell attachment, indicating that biological interactions involve complexities beyond simple wettability [13].

For comprehensive surface characterization, WCA should be integrated with complementary analytical techniques:

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Provides quantitative elemental and chemical state information about the top 1-10 nm of a surface [13] [11].

- Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS): Offers ultra-high sensitivity for detecting organic contamination and mapping chemical distributions [13].

- Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM): Characterizes surface topography and nanoscale roughness that influences wettability [11].

Diagram: WCA Interpretation and Key Limitations. Multiple factors influence WCA, which has specific limitations for surface characterization.

Water contact angle measurement remains an indispensable technique for surface cleanliness research, providing a rapid, sensitive, and quantitative method for detecting contamination and characterizing surface chemistry. The transition from hydrophilic to hydrophobic states, as revealed by WCA, offers critical insights into the molecular-level condition of surfaces, enabling researchers to validate cleaning processes, monitor surface aging, and ensure material performance. While methodological rigor is essential for reproducible results, and complementary techniques are needed for complete surface analysis, WCA stands as a fundamental first step in the researcher's analytical toolkit for surface quality assessment.

The Critical Link Between Low Contact Angles and Optically Clean Surfaces

In the realm of high-precision optics and pharmaceutical development, surface cleanliness transcends ordinary cleanliness standards. Optical surface cleanliness refers to a state of molecular-level purity where surfaces are free from contaminants that could interfere with light transmission, reflection, or subsequent coating adhesion. This specialized form of cleanliness is critical across numerous applications, from surgical endoscope lenses to coating substrates for drug delivery systems [14]. The fundamental challenge researchers face lies in quantitatively assessing this invisible cleanliness standard—a challenge where water contact angle (WCA) measurement has emerged as an indispensable tool.

When a water droplet contacts a properly cleaned optical surface, it exhibits predictable spreading behavior characterized by a low contact angle (typically <30°). This low angle reflects the high surface energy of the clean substrate, which readily interacts with the water droplet. Conversely, contaminated surfaces, often covered with hydrophobic organic residues, exhibit high contact angles where water beads up rather than spreads [3] [10]. This quantitative relationship makes contact angle measurement a sensitive indicator of surface condition, capable of detecting monolayer contamination that would otherwise remain invisible to conventional inspection methods.

Theoretical Foundation: The Science Behind Contact Angle and Cleanliness

Wettability and Surface Energy Fundamentals

The theoretical basis for using contact angle to assess cleanliness stems from classical surface science. According to Young's equation, the contact angle (θ) formed at the solid-liquid-vapor interface is determined by the balance between three interfacial tensions: solid-vapor (γ~sv~), solid-liquid (γ~sl~), and liquid-vapor (γ~lv~) [15]:

γ~sv~ = γ~sl~ + γ~lv~cosθ

This equation establishes the direct relationship between contact angle and the surface energy of the solid (γ~sv~). For optically clean surfaces with high surface energy, the difference between γ~sv~ and γ~sl~ is large, resulting in a small θ value [15] [16]. This thermodynamic foundation validates contact angle as a quantitative measure of surface cleanliness and readiness for subsequent processing.

Surface contamination typically introduces low-energy organic layers that dramatically reduce the apparent surface energy of the substrate. Even monomolecular layers of contamination can significantly increase the water contact angle by disrupting the molecular interactions between the water droplet and the high-energy substrate [3]. This sensitivity makes contact angle measurement particularly valuable for detecting trace contamination that could compromise optical performance or coating adhesion.

Beyond Static Measurements: The Role of Hysteresis

While static contact angle provides valuable initial information, comprehensive surface characterization requires dynamic contact angle analysis, which includes advancing (θ~A~) and receding (θ~R~) angles along with their difference, known as contact angle hysteresis [17] [15]. For optically clean surfaces, both advancing and receding angles remain low, with minimal hysteresis—typically less than 10° [3].

Contact angle hysteresis arises primarily from surface chemical heterogeneity and topographical variations [17] [15]. On contaminated surfaces, the receding angle often shows greater sensitivity to hydrophobic domains, making it a particularly useful indicator for detecting patchy contamination that might not significantly affect the static contact angle [3]. This sophisticated analysis provides researchers with deeper insights into the distribution and nature of surface contaminants.

Comparative Analysis of Contact Angle Measurement Techniques

Methodological Comparison

Researchers investigating optical surface cleanliness can select from several well-established contact angle measurement techniques, each with distinct advantages and limitations for specific experimental scenarios.

Table 1: Comparison of Contact Angle Measurement Techniques

| Method | Working Principle | Optimal Use Cases | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optical Tensiometry (Sessile Drop) [17] [16] | Analysis of droplet profile using side-view imaging | Smooth, homogeneous surfaces; basic cleanliness verification | - Direct visualization- Simple experimental setup- Suitable for static and dynamic measurements | - Affected by surface roughness- Requires relatively flat, uniform surfaces |

| Wilhelmy Plate Method [17] | Measurement of force during immersion/emersion | Fibers, membranes, and uniform geometric samples | - Averages over entire sample- Provides inherent advancing/receding angles | - Requires specific sample geometry- Not suitable for coated-only surfaces |

| Tilting Plate Method [17] [15] | Analysis of droplet deformation on tilted surfaces | Hysteresis measurement; roll-off angle determination | - Direct hysteresis measurement- Mimics practical conditions | - More complex setup- Potential influence of inertia |

| Captive Bubble Method [17] | Analysis of air bubble under immersed surface | Highly hydrophilic surfaces; in-situ conditions | - Ideal for superhydrophilic surfaces- Mimics submerged applications | - Requires immersion cell- More complex setup |

Specialized Measurement Approaches

Beyond conventional methods, specialized techniques address unique challenges in optical surface characterization:

Roughness-Corrected Contact Angle: This approach accounts for surface topography effects using the Wenzel equation, which relates the measured contact angle to the theoretical angle through a roughness ratio (r = actual/projected surface area) [17]. This is particularly relevant for optically functional surfaces with engineered microstructures.

Picoliter Droplet Measurements: For small optical components or patterned surfaces, picoliter dispensers can produce droplets as small as 30μm in diameter, enabling measurements on confined areas as small as 0.1-0.3mm [17] [18]. This approach is invaluable for micro-optical elements and patterned substrates where traditional microliter droplets would exceed the region of interest.

Experimental Protocols for Optical Surface Cleanliness Assessment

Standardized Measurement Procedure

To ensure reproducible contact angle measurements for optical cleanliness verification, researchers should follow this standardized protocol:

Sample Preparation: Begin with representative substrate materials (typically 1cm × 1cm or larger). Handle samples with clean gloves or vacuum tweezers to prevent contamination. If comparing cleaning methods, divide samples from the same batch into experimental groups [3].

Surface Cleaning: Apply the cleaning protocol under investigation (e.g., plasma treatment, solvent washing, or ultrasonic cleaning). For metal surfaces, document cleaning sequences as even "clean" metals may instantly react with air molecules, making theoretical surface energies impossible to measure in practice [3].

Baseline Establishment: Measure reference samples with known cleanliness states to establish expected contact angle ranges. Clean glass typically exhibits angles <10°, while properly cleaned metals show angles <30° [3] [19].

Droplet Deposition: Using an automated dispensing system, place a 2-5μL deionized water droplet on the surface. Ensure consistent deposition parameters (needle size, deposition height, and velocity) to minimize measurement variability [16].

Image Acquisition: Capture the droplet image within 1-3 seconds of deposition using a high-resolution camera with appropriate backlighting. Ensure the entire droplet profile and baseline are in focus with high contrast [16].

Angle Calculation: Analyze the droplet image using appropriate fitting algorithms (Young-Laplace, circle, or polynomial fits). For asymmetric droplets, measure both left and right contact angles and report the average [17] [16].

Advanced Characterization Protocols

For comprehensive surface analysis, researchers should supplement static contact angle with these advanced protocols:

Dynamic Contact Angle Measurement:

- Using the needle method, gradually increase the droplet volume (typically 0.1-0.5μL/sec) while recording to determine the advancing angle [17].

- Subsequently decrease the volume at the same rate to measure the receding angle [17].

- Calculate hysteresis as θ~A~ - θ~R~. For optically clean surfaces, hysteresis should be minimal (<10°) [17] [15].

Surface Energy Calculation:

- Measure contact angles with at least three liquids with known polar and dispersive surface tension components (typically water, diiodomethane, and ethylene glycol) [18].

- Apply the Owens-Wendt-Rabel-Kaeble (OWRK) method to calculate the total surface energy and its polar and dispersive components [19] [18].

- Clean, high-energy surfaces typically exhibit total surface energies >40 mN/m with significant polar components [3].

Research Reagent Solutions for Contact Angle Studies

Table 2: Essential Research Materials for Contact Angle Measurements

| Category | Specific Items | Research Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Liquids [18] | Deionized water, Diiodomethane, Ethylene glycol | Surface energy calculation; wettability studies | - ≥99% purity recommended- Store in sealed containers- Degas before measurements |

| Cleaning Reagents [3] [14] | Isopropyl alcohol, Acetone, Oxygen plasma, Piranha solution | Surface preparation; cleaning efficacy studies | - Sequence matters for multi-step cleaning- Plasma parameters affect results- Safety protocols critical for piranha |

| Substrate Materials [3] [19] | Fused silica, Borosilicate glass, Silicon wafers, Medical-grade metals | Method validation; substrate-specific studies | - Document surface roughness- Control storage conditions- Note substrate surface energy |

| Calibration Standards | Pre-treated reference slides, Certified surfaces | Instrument calibration; method validation | - Regular calibration schedule- Document storage conditions- Track expiration dates |

Comparative Performance Data: Contact Angle Across Surface Conditions

Empirical data demonstrates the sensitivity of contact angle measurement for detecting surface contamination and verifying cleaning effectiveness across different material classes.

Table 3: Contact Angle Variation with Surface Condition and Cleaning Methods

| Surface Material | Initial State (Contaminated) | After Basic Cleaning | After Advanced Cleaning | Cleaning Methods Employed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copper [3] | 65-85° | 45-60° | 15-25° | Ultrasonic soap → Acid etching → Plasma cleaning |

| Nickel [3] | 60-80° | 40-55° | 10-20° | Ultrasonic soap → Acid etching → Plasma cleaning |

| Glass [19] | 40-60° | 20-35° | <10° | Solvent wash → Plasma treatment → UV ozone |

| PTFE [20] | 95-110° | 90-100° | 85-95° | Surfactant cleaning → Solvent rinse |

| Superhydrophobic Coating [19] | - | - | 158.2±0.7° | Fluorine-free bilayer fabrication |

The data clearly demonstrates that properly cleaned high-energy surfaces (metals and glass) consistently achieve low contact angles, while inherently low-energy materials like PTFE maintain high angles even after cleaning. Superhydrophobic coatings represent the extreme opposite of clean high-energy surfaces, with intentionally engineered high contact angles for self-cleaning applications [19].

Limitations and Complementary Analytical Techniques

While contact angle measurement provides exceptional sensitivity to surface chemical state, researchers should recognize its limitations:

- Spatial averaging provides information about the average surface condition but may miss localized contamination [10].

- Subsurface contamination that doesn't affect surface chemistry may not be detected [10].

- Surface roughness significantly influences measurements and requires specialized correction methods [17].

- Molecular specificity is limited—contact angle indicates contamination but doesn't identify specific contaminants [10].

For comprehensive surface characterization, researchers should consider integrating contact angle with complementary techniques:

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Provides elemental and chemical state information for contaminant identification [10].

- Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM): Maps topographical features and nanoscale heterogeneity [10].

- Optical Emission Spectroscopy: Useful for in-process monitoring of plasma cleaning treatments [21].

Water contact angle measurement stands as an indispensable tool in the researcher's arsenal for quantifying optical surface cleanliness. Its exceptional sensitivity to molecular-level contamination, rapid implementation, and quantitative output make it ideal for comparing cleaning methods, establishing cleanliness standards, and maintaining quality control across diverse optical applications. As optical technologies advance toward increasingly stringent performance requirements, the critical link between low contact angles and optically clean surfaces will continue to drive innovation in both measurement methodologies and cleaning processes.

The experimental data and methodologies presented in this guide provide researchers with a robust framework for implementing contact angle measurements in their optical cleanliness verification protocols. By selecting appropriate measurement techniques, following standardized protocols, and understanding both the capabilities and limitations of the method, scientists can leverage this powerful technique to advance optical system performance across pharmaceutical, medical, and industrial applications.

Surface cleanliness is paramount in optical research and manufacturing, where trace-level contaminants can significantly alter interfacial properties and compromise performance. This guide objectively compares the sensitivity of water contact angle measurement against other surface analysis techniques for detecting molecular contamination. We present quantitative experimental data demonstrating how sub-monolayer contaminants dramatically shift droplet behavior, supported by standardized protocols that enable researchers to correlate macroscopic wettability changes with microscopic surface condition.

In optical surface research, cleanliness is not merely about visual perfection but involves molecular-level purity that directly affects performance. Trace contaminants—including skin oils, dust particulates, and process residues—form molecular layers that fundamentally alter how light interacts with surfaces and how liquids wet them. These changes manifest quantitatively through water contact angle measurements, which provide a rapid, sensitive method for detecting surface contamination that often eludes other analytical techniques.

The significance of droplet behavior as a contamination indicator stems from direct molecular interaction at the three-phase contact line. Even fractional monolayer coverage of hydrophobic contaminants on theoretically high-energy surfaces drastically increases water contact angles, while hydrophilic contaminants produce the opposite effect. This sensitivity makes contact angle measurement an indispensable tool for quality control in optical manufacturing, pharmaceutical development, and surface science research.

Experimental Protocols for Contamination Detection

Standardized Contact Angle Measurement Procedure

Reliable contamination detection requires strict adherence to standardized measurement protocols. The following procedure, adapted from established methodologies, ensures reproducible results [22] [7]:

Sample Preparation: Cut samples to standardized dimensions (typically 15mm wide strips). Clean surfaces with appropriate solvents (isopropanol, acetone) using lint-free cloths to remove gross contamination. Handle samples with tweezers or gloves to prevent fingerprint deposition [7].

Static Contact Angle Measurement:

- Utilize an optical tensiometer/goniometer with high-speed camera system

- Dispense 5-8 μL high-purity deionized water (surface tension: 72.8±0.5 mN/m at 20°C) via precision syringe

- Position needle 1-2mm above surface, form pendant droplet, and gently contact surface

- Capture image within 10-15 seconds of deposition to minimize evaporation effects

- Analyze droplet profile using Young-Laplace fitting in specialized software [17] [7]

Dynamic Contact Angle Measurement:

Environmental Control: Maintain temperature at 23±2°C and constant humidity throughout measurements to prevent environmental artifacts [7].

Replication: Perform minimum 5-10 measurements per sample at different locations, spacing measurement points至少25mm apart [7].

Advanced Techniques for Challenging Surfaces

For rough or porous substrates that complicate traditional measurements, specialized approaches are required:

Roughness Correction: Measure surface topography simultaneously with contact angle using integrated profilometry, then apply Wenzel equation corrections to account for roughness contributions [17].

Powder Characterization: Compress powders into tablets using hydraulic presses or create thin powder layers on adhesive substrates before measurement [23].

Micro-Droplet Methods: Employ picoliter dispensers and high-magnification optics for measurements on small or patterned surfaces where standard droplets are impractical [17].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for contamination detection via contact angle measurement. Strict protocol adherence ensures reproducible results sensitive to molecular-level surface contaminants [22] [7].

Quantitative Data: Contamination Impact on Droplet Behavior

Metallic Surface Contamination

Metal surfaces exhibit extreme sensitivity to organic contamination due to their inherently high surface energy. The table below demonstrates how successive cleaning stages remove contaminants and progressively reduce water contact angles on metal surfaces [3]:

Table 1: Water contact angle changes on metal surfaces through cleaning stages

| Surface Material | Pre-Cleaning CA (°) | After Ultrasonic Cleaning CA (°) | After Plasma Cleaning CA (°) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Copper | 74° | 16° | 8° |

| Nickel | 63° | 18° | 9° |

Polymeric Surface Contamination

Polymer surfaces present more complex wettability behavior, where receding contact angles often show greater sensitivity to contamination than static measurements:

Table 2: Advancing and receding contact angles on polymers before and after cleaning

| Polymer Type | Condition | Advancing CA (°) | Receding CA (°) | Hysteresis (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teflon | Contaminated | 108° | 65° | 43° |

| Teflon | Cleaned | 120° | 95° | 25° |

| Polypropylene | Contaminated | 95° | 45° | 50° |

| Polypropylene | Cleaned | 102° | 85° | 17° |

The data reveals that while static angles on Teflon increased post-cleaning (consistent with contaminant removal), the receding angle provided more definitive cleanliness verification, increasing from 65° to 95° [3]. This highlights the critical importance of dynamic contact angle measurements for accurate contamination assessment.

Mineral Surface Heterogeneity Effects

Natural mineral surfaces demonstrate how localized heterogeneity affects wettability measurements. Using combined argon ion polishing and atomic force microscopy (Ar+-AFM), researchers obtained more consistent contact angle data (20.1°±2.5°) on K-feldspar homogeneous areas, versus highly variable results (10°-51°) with traditional optical methods on heterogeneous surfaces [24]. This underscores how conventional measurements can be confounded by surface heterogeneity, potentially masking contamination effects.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential reagents and equipment for contamination detection via contact angle

| Item | Function | Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Optical Tensiometer | Primary measurement instrument | High-speed camera, precision dispensing system, environmental enclosure [17] |

| Deionized Water | Primary probe liquid | High-purity (18.2 MΩ·cm), surface tension verification (72.8±0.5 mN/m at 20°C) [7] |

| Precision Syringes | Liquid dispensing | Calibrated volume, fine-gauge needles (e.g., 22-26G) for consistent droplet formation [7] |

| Solvent Cleaning Kit | Surface preparation | HPLC-grade isopropanol, acetone, lint-free wipes, gloves [7] |

| Reference Materials | Calibration | Surfaces with known contact angles (e.g., clean silicon wafer, Teflon) [22] |

| Picoliter Dispenser | Micro-scale measurements | Essential for small features, fiber analysis, patterned surfaces [17] |

| Surface Roughness Module | Topography correlation | Combined profilometry for roughness-corrected contact angles [17] |

| Anti-static Equipment | Sample handling | Ionizer guns for polymer films to prevent electrostatic artifacts [7] |

Comparative Analysis: Contact Angle vs. Alternative Techniques

While numerous surface analysis techniques exist, contact angle measurement offers unique advantages for contamination detection:

Sensitivity Comparison: Contact angle detects sub-monolayer surface contamination (0.1-1nm thickness), comparable to XPS and ToF-SIMS but with significantly lower cost and complexity [3].

Throughput Advantage: Contact angle measurements require seconds to minutes versus hours for ultra-high vacuum techniques, enabling rapid quality control decisions [4].

Limitations: Contact angle provides indirect chemical information compared to spectroscopic methods. It detects contamination presence but not specific chemical identity.

Complementary Approach: For complete surface characterization, contact angle serves as an ideal screening method followed by targeted spectroscopic analysis of suspect samples.

Figure 2: Contamination detection techniques comparison. Contact angle measurement provides sensitive, rapid detection of molecular-level surface changes caused by contaminants [24] [3] [4].

Water contact angle measurement stands as an exceptionally sensitive technique for detecting trace surface contaminants that dramatically alter droplet behavior. Through standardized protocols and proper data interpretation—particularly leveraging dynamic contact angle information—researchers can identify molecular-level contamination with precision rivaling sophisticated surface analysis instruments. The methodology provides an optimal balance of sensitivity, practicality, and quantitative output for optical surface cleanliness verification across research and industrial applications.

Within optical surface cleanliness research, the imperative to detect molecular-level contaminants without altering the test surface has driven the adoption of advanced analytical techniques. This guide objectively compares the performance of Water Contact Angle (WCA) measurement against traditional alternatives for identifying invisible residues that compromise surface quality in critical applications. While traditional methods like the water break test offer simplicity, quantitative WCA analysis provides superior sensitivity to both hydrophobic and hydrophilic contaminants, non-destructive testing capability, and data-driven traceability essential for modern quality systems. Experimental data from controlled studies demonstrate WCA's capability to detect contaminant layers as thin as 2-3 molecules, with measurement precision exceeding subjective visual methods by factors of 5-10x. The integration of WCA with machine learning platforms further enhances its predictive capability for long-term surface performance, positioning it as an indispensable tool for research and development professionals requiring non-destructive surface characterization.

Surface contamination at the molecular level represents a formidable challenge in pharmaceutical development, medical device manufacturing, and optical component production. These invisible residues—including silicone oils, surfactant layers, machining lubricants, and processing aids—often evade visual inspection yet profoundly impact adhesion, coating uniformity, and performance reliability. The limitations of traditional cleanliness assessment methods have created a technological gap in non-destructive surface characterization, particularly for detecting contaminants that do not manifest as visible films or particulates.

Water Contact Angle measurement has emerged as a powerful solution to this challenge, transitioning from a specialized research technique to a validated production tool. WCA operates on fundamental principles of surface science, measuring the angle formed at the solid-liquid-gas interface to quantify surface energy and wettability. This deceptively simple measurement provides a sensitive probe of the outermost molecular layers of a surface, detecting chemical heterogeneity that other methods miss. The technique's non-destructive nature preserves sample integrity while providing quantitative data that correlates directly with adhesion performance and coating quality.

Comparative Analysis of Surface Cleanliness Assessment Methods

Performance Comparison of Primary Assessment Techniques

Table 1: Quantitative comparison of surface cleanliness assessment methods

| Method | Detection Principle | Sensitivity | Quantitative Output | Contaminants Detected | Throughput | Capital Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water Contact Angle | Liquid wetting behavior | 2-3 molecular layers | Numerical angle (°) | Hydrophobic & hydrophilic | Medium-high | Medium |

| Water Break Test | Visual water film continuity | Macroscopic films | Pass/fail visual assessment | Hydrophobic only | Very high | Very low |

| Dyne Pens | Surface tension inks | ~10 mN/m resolution | Semi-quantitative (mN/m) | Limited range | High | Low |

| FTIR Spectroscopy | Molecular absorption | Monolayers | Spectral peaks | Chemical identification | Low | High |

| XPS (ESCA) | Electron emission | 1-10 nm | Atomic composition | Elemental specificity | Very low | Very high |

Technical Limitations of Traditional Methods

The water break test, despite its historical prevalence and operational simplicity, suffers from critical limitations in modern precision manufacturing environments. As a purely subjective visual assessment, it depends entirely on technician interpretation, yielding results that vary significantly between operators [25]. The method fundamentally detects only hydrophobic contaminants like oils and greases, while remaining blind to hydrophilic residues such as surfactants or cleaning agent remnants that can equally compromise adhesion [25]. Perhaps most concerning is its potential to introduce contamination through non-purified test water, inadvertently depositing minerals, organics, or particulates on the validated surface [25].

Dyne pens and similar surface tension test inks provide slightly more granularity than water break tests but remain semi-quantitative at best. These methods introduce their own contaminants to the surface through the testing inks, rendering the tested area unusable for subsequent processing. Their results are influenced by application pressure and technique, introducing operator-dependent variables that compromise measurement repeatability. Like the water break test, they offer no permanent record or traceable data for process validation or quality audits [10].

Water Contact Angle Measurement: Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Fundamental Measurement Principles

Water Contact Angle measurement quantifies the wettability of a surface by analyzing the interface where water, solid surface, and air meet. The contact angle (θ, theta) is geometrically defined as the angle formed by a liquid at the three-phase boundary where liquid, gas, and solid intersect [17]. Low contact angles (<30°) indicate high surface energy and wettability, characteristic of clean, reactive surfaces ready for bonding or coating. High contact angles (>90°) signal low surface energy surfaces, typically contaminated with hydrophobic substances or improperly prepared for adhesion processes [10].

The measurement sensitivity stems from its ability to probe the top 2-3 molecular layers of a surface, detecting chemical changes invisible to the naked eye [25]. Even trace contaminants covering less than 5% of a surface can produce measurable changes in contact angle values, providing early warning of process deviation before adhesion failures occur.

Core Measurement Methodologies

Static Sessile Drop Measurement The most common WCA approach involves depositing a precise water droplet (typically 2-10 μL) onto the surface and optically measuring the static angle using a goniometer [17]. The droplet image is analyzed with fitting algorithms (Young-Laplace, circle, or polynomial) to determine the contact angle at the three-phase boundary. This method provides a rapid, quantitative assessment of surface wettability and is suitable for relatively smooth, homogeneous surfaces [17].

Dynamic Contact Angle Analysis For more comprehensive surface characterization, dynamic measurements capture advancing (θA) and receding (θR) angles, whose difference defines contact angle hysteresis [17]. The needle method gradually increases droplet volume to measure advancing angle, then decreases volume for receding angle [17]. The tilting method places a droplet on a surface that is progressively tilted, measuring advancing angle at the droplet front and receding angle at the back just as movement begins [17]. Contact angle hysteresis and the related roll-off angle (the tilt angle at which droplets begin to move) provide critical information about surface heterogeneity and droplet adhesion [17] [26].

Table 2: Experimental protocols for WCA measurement techniques

| Method | Sample Preparation | Measurement Parameters | Data Analysis | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Static Sessile Drop | Clean, dry, flat surface | 2-10 μL purified water, ambient conditions | Young-Laplace fitting | Quick cleanliness verification |

| Advancing/Receding (Needle) | Uniform surface chemistry | Controlled volume change 0.1-1 μL/sec | Hysteresis calculation (θA - θR) | Surface heterogeneity analysis |

| Tilting Plate | Rigid, mountable samples | Tilt rate 0.5-2°/sec, droplet volume 5-15 μL | Roll-off angle determination | Self-cleaning surfaces, drag reduction |

| Wilhelmy Plate | Uniform, rectangular samples | Known perimeter, immersion speed 0.1-5 mm/min | Force balance calculation | Fibers, porous materials, average properties |

Experimental Workflow for Contamination Detection

The following diagram illustrates the standardized experimental workflow for detecting invisible residues through WCA measurement:

Advanced Techniques for Challenging Surfaces

Roughness-Corrected Measurements Surface roughness significantly influences apparent contact angles through mechanisms described by Wenzel (complete penetration into roughness grooves) and Cassie-Baxter (composite air-solid interface) models [17]. Roughness-corrected measurements combine topographical analysis with contact angle data using the roughness ratio (actual versus projected surface area) to normalize wettability measurements [17].

Specialized Sample Protocols

- Fibers and thin materials: Employ picoliter dispensers for droplets with ~30μm diameter or meniscus measurement techniques [17]

- Powders and porous materials: Utilize Washburn method for capillary penetration analysis or compressed tablet measurements [17]

- Small or curved areas: Implement picoliter dispensing with high-magnification optics for features below standard droplet size [17]

- Extreme conditions: Employ temperature-controlled stages (-40°C to 250°C) or high-pressure chambers (up to 400 bar) for specialized applications [17]

Experimental Data: WCA Sensitivity to Specific Contaminants

Quantitative Detection Thresholds

Table 3: WCA response to common manufacturing contaminants

| Contaminant Type | Base Surface | Clean Surface WCA | Contaminated WCA | Detection Threshold | Adhesion Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silicone Oil | Stainless steel | 65° ± 3° | 105° ± 8° | 0.2 mono-layer | Coating delamination |

| Fatty Acids | Glass | 42° ± 2° | 85° ± 5° | 0.5 mono-layer | 80% bond strength reduction |

| Machine Oils | Aluminum | 72° ± 4° | 112° ± 6° | 2 nm film | Paint adhesion failure |

| Surfactant Residues | Polymers | 75° ± 3° | 45° ± 7° | 0.3 mono-layer | Coating cratering |

| Oxidation Layer | Copper | 65° ± 2° | 95° ± 4° | 5 nm thickness | Solderability decrease |

Controlled contamination studies demonstrate WCA's exceptional sensitivity to surface chemistry changes. On stainless steel surfaces, silicone oil contamination as thin as 0.2 monolayers produces measurable WCA increases from 65° to over 105°, providing early detection long before adhesion failures manifest [10]. Similarly, surfactant residues that remain invisible to water break testing produce dramatic WCA decreases from 75° to 45° on polymer surfaces, signaling hydrophilic contamination that can cause coating defects [25].

Correlation with Bond Performance

The relationship between WCA measurements and adhesion performance follows a well-established non-linear correlation. Surfaces with WCAs below 40° typically exhibit excellent adhesion for most coatings and adhesives, while those exceeding 80° present increasing risk of bonding failures. The most critical process control window often falls between 50°-70°, where small WCA changes signal significant contamination events requiring intervention [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential materials and reagents for WCA contamination studies

| Item | Specifications | Application | Critical Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrapure Water | Type I (18.2 MΩ·cm), TOC < 5 ppb | Reference liquid | Eliminates water-born contamination variables |

| Certified Clean Substrates | Mirror-finish stainless steel, silicon wafers | Measurement baseline | Provides validated reference surfaces |

| Contaminant Standards | Certified silicone oil, fatty acid, alkane solutions | Controlled contamination studies | Enables quantitative dose-response calibration |

| Precision Syringes | 1-10 μL, PTFE-coated tips | Droplet deposition | Ensures consistent droplet volume and placement |

| Optical Goniometer | 0.1° resolution, automated dispensing | Angle measurement | Provides quantitative, repeatable data |

| Surface Energy Kits | Multiple liquids with known surface tensions | Surface energy calculation | Enables surface energy component analysis |

Emerging Applications and Machine Learning Integration

Advanced WCA methodologies are being integrated with machine learning platforms to predict long-term surface behavior from short-term measurements. Recent studies demonstrate that ML algorithms (Random Forest, XGBoost) can accurately forecast contact angle stability under various environmental stressors by training on experimental degradation data [27] [28]. These models analyze complex, non-linear relationships between coating composition, application parameters, and WCA performance that traditional statistical methods often miss.

In co-sputtered coating development, ML models have reduced parameter optimization from months of iterative testing to days of predictive modeling. The Random Forest algorithm has demonstrated particular efficacy in predicting WCA of co-sputtered coatings, accurately forecasting superhydrophilic behavior (WCA < 5°) based on deposition parameters [27]. Similar approaches successfully predict the stability of superhydrophobic graphene-based coatings on copper substrates under mechanical stress and corrosive conditions [28].

The following diagram illustrates the integration of WCA measurement with machine learning for predictive surface analysis:

Water Contact Angle measurement represents a critical advancement in non-destructive surface characterization, providing sensitivity to invisible residues that traditional methods cannot detect. While the water break test retains limited applicability for gross contamination checks in non-critical applications, WCA offers quantitative, reproducible data essential for modern manufacturing and research environments. The technique's ability to probe the top molecular layers of a surface without alteration makes it particularly valuable for pharmaceutical development, medical device manufacturing, and optical surface research where sample preservation is paramount.

The integration of WCA with advanced analytical platforms and machine learning algorithms represents the future of predictive surface science, enabling researchers to forecast long-term performance from immediate measurements. As surface cleanliness requirements continue to tighten across industries, WCA methodology stands as an indispensable tool for the detection and quantification of invisible residues that compromise product quality and performance.

Measuring for Cleanliness: Methodologies and Direct Applications for Optical Surfaces

The contact angle is a fundamental quantitative measure used to evaluate the wettability of a solid surface by a liquid. It is defined as the angle formed between the tangent to the liquid-vapor interface and the tangent to the solid-liquid interface at the three-phase (solid-liquid-vapor) contact line [29]. The value of this angle, typically denoted as θ (theta), is a direct consequence of the balance between the cohesive forces within the liquid and the adhesive forces between the liquid and the solid [30]. In practical terms, a small contact angle (θ < 90°) signifies that the liquid spreads readily over the surface, characterizing a hydrophilic or wetting state. Conversely, a large contact angle (θ > 90°) indicates that the liquid beads up, characterizing a hydrophobic or non-wetting state [31] [29]. For instance, a contact angle of 0° denotes complete wetting, while angles exceeding 150° are associated with superhydrophobic surfaces [31].

The measurement of contact angle is not merely an academic exercise; it is a critical diagnostic tool in optical surface cleanliness research and numerous industrial and scientific fields. The wettability of a surface directly influences phenomena such as coating uniformity, adhesion, cleaning efficacy, and lubricity [31] [32]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding and controlling surface wettability is essential for applications ranging from the development of biocompatible implants and contact lenses to the optimization of drug delivery surfaces and diagnostic platforms [33] [34]. The three techniques detailed in this guide—Sessile Drop, Captive Bubble, and Wilhelmy Plate—represent the core methodologies for determining this crucial parameter, each with distinct principles, advantages, and limitations.

The following table provides a consolidated, data-driven comparison of the three primary contact angle measurement techniques to guide method selection.

Table 1: Comprehensive comparison of sessile drop, captive bubble, and Wilhelmy plate methods.

| Feature | Sessile Drop | Captive Bubble | Wilhelmy Plate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Principle | Analyzes shape of a liquid droplet seated on a solid surface [30]. | Analyzes shape of an air bubble attached to a solid surface submerged in liquid [30] [33]. | Measures force exerted on a solid sample as it is immersed/withdrawn from liquid [30] [32]. |

| Measured Angle | Considered close to the advancing contact angle [33]. | Considered close to the receding contact angle [33]. | Directly measures both advancing (immersion) and receding (emersion) angles [34]. |

| Sample Environment | Ambient air (can lead to dehydration) [34]. | Fully immersed in liquid (preserves hydrated state) [33] [34]. | Liquid is contained in a vessel; sample is cycled in/out [30]. |

| Key Advantages | Fast, easy, versatile for sample shapes [30] [34]. | Ideal for hydrated/hydrophilic surfaces; prevents dehydration [33] [34]. | Provides highly accurate and reproducible data; measures average value and hysteresis [34] [32]. |

| Key Limitations | Susceptible to dehydration; subjective analysis for some models [34]. | Time-consuming bubble alignment; requires transparent liquid [34]. | Requires sample with uniform geometry and known perimeter; more complex setup [30] [34]. |

| Best For | Routine analysis, quality control, samples with irregular surfaces [32]. | Bio-medical materials, contact lenses, hydrogels, and any application where the surface is naturally hydrated [33] [34]. | High-accuracy research on materials with regular geometry (e.g., films, fibers); dynamic wetting studies [34] [32]. |

Detailed Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Sessile Drop Method

The sessile drop technique is the most widely used optical method for contact angle measurement due to its straightforward setup and minimal sample preparation [30] [34].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: The solid sample is placed on a level stage. For consistent results, the surface may be blotted or cleaned according to protocol, though this can risk dehydration [34].

- Dispensing: A precise volume of probe liquid (e.g., water) is dispensed from a syringe equipped with a flat-tipped needle onto the sample surface, forming a pendant drop that transfers to become a sessile drop [34].

- Image Capture: A high-resolution camera, aligned orthogonally to the sample surface, captures an image of the static droplet immediately after deposition to minimize evaporation effects.

- Analysis: The contact angle is determined by software analysis of the droplet image. Common algorithms include:

- Tangent Method: Fits a tangent line to the droplet contour at the three-phase contact point. This is a local method and works even with needle-in-drop setups, but can be subjective [35].

- Circle Fitting / θ/2 Method: Assumes the droplet is a spherical cap and fits a circle to its outline. This is best for small contact angles (<20°) and small volumes where gravity is negligible [35].

- Young-Laplace Fitting: Fits the entire droplet profile to the Young-Laplace equation, which accounts for gravity-induced distortion. This is the most accurate method for larger droplets and contact angles >60°, but requires axisymmetric drops [35].

Captive Bubble Method

The captive bubble method is essentially the inverse of the sessile drop technique and is particularly valuable for studying hydrophilic and hydrated surfaces [33] [34].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Hydration: The solid sample is fully immersed and allowed to equilibrate in a transparent cell filled with the probe liquid (often an aqueous solution). This ensures the surface remains in a hydrated state throughout the measurement [33].

- Bubble Formation: A syringe with a J-shaped needle is positioned beneath the sample surface. A small bubble of air (or another immiscible gas/fluid) is injected from the syringe until it is "captured" on the underside of the sample surface [30] [33].

- Image Capture: A camera captures an image of the attached bubble from the side.

- Analysis: The contact angle is analyzed from the bubble image. Because the bubble is a gas-liquid interface in a liquid medium, the angle measured (θbubble) is the supplement to the conventional water-in-air angle (θwater). Therefore, θwater = 180° - θbubble [33]. The Laplace-Young equation fit is often the preferred analysis method here, especially for hydrophilic surfaces where bubble shapes are highly distorted [33] [35].

A modified captive bubble method has been developed to improve accuracy. This version places the entire setup in a pressure chamber. After the bubble is formed, the needle is retracted, and precise pressure changes in the chamber are used to control the bubble size for advancing and receding angle measurements, eliminating the interference of the needle [36].

Wilhelmy Plate Method

The Wilhelmy plate method is a force tensiometry technique that provides dynamic contact angle data [30] [32].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: A solid sample with a known, uniform geometry (typically a rectangular plate or a cylindrical rod) is suspended from a highly sensitive microbalance. The perimeter (P) of the sample at the immersion point must be precisely known [30] [32].

- Liquid Preparation: A vessel containing the probe liquid, with a known surface tension (γLV), is raised on a movable stage.

- Force Measurement: The liquid vessel is raised at a constant rate, immersing the sample to a set depth, and then lowered to withdraw it. The microbalance continuously records the force (F) on the sample during this cycle.

- Data Analysis: The force data is used to calculate the contact angle via the Wilhelmy equation:

- F = γLV · P · cosθ Rearranging for the contact angle: θ = cos-1[F / (γLV · P)] The force during immersion is used to calculate the advancing contact angle, while the force during withdrawal gives the receding contact angle. The difference between these two values is the contact angle hysteresis, which provides insights into surface heterogeneity and roughness [34] [32].

Decision Workflow and Application Context

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for selecting the most appropriate measurement technique based on sample properties and research objectives.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

A successful contact angle measurement experiment relies on more than just the core instrument. The following table details key reagents and materials essential for preparing and conducting these analyses.

Table 2: Key research reagents and materials for contact angle measurement.

| Item | Function / Purpose | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Probe Liquids | High-purity liquids (e.g., water, diiodomethane, ethylene glycol) used to probe surface energy and wettability. | Purity is critical to avoid contamination affecting surface tension. Multiple liquids are required for surface free energy calculations [37]. |

| Sample Preparation Kits | Tools for cleaning and pre-treating sample surfaces (e.g., plasma cleaners, UV ozone units, solvent baths). | Ensures a clean, contaminant-free surface for reliable baseline measurements. Plasma treatment can temporarily increase hydrophilicity [31]. |

| Precision Syringes & Needles | Used to generate consistent droplets (sessile drop) or bubbles (captive bubble). | Flat-tipped needles (e.g., J-shaped) are essential for proper droplet detachment and bubble capture [33] [34]. |

| Software Analysis Modules | Algorithms for image (sessile drop, captive bubble) or force (Wilhelmy plate) data processing. | Selection of correct model (e.g., Tangent, Circle, Laplace-Young) is vital for accuracy, depending on angle and droplet shape [35]. |

| Standard Reference Samples | Surfaces with known, stable contact angles (e.g., Teflon for hydrophobic, glass for hydrophilic). | Used for daily instrument calibration and validation to ensure measurement accuracy and repeatability. |

Advanced Topics in Contact Angle Measurement

Data Analysis and Theoretical Models

The accuracy of optical contact angle measurements is heavily dependent on the chosen analysis model. The Laplace-Young equation represents the most rigorous approach, as it accounts for the entire droplet shape under the influence of gravity [35] [38]. Solving this equation allows for the precise calculation of contact angle, even for large droplets where gravitational sag is significant. Simpler models, such as the Circle Fitting (or θ/2) method, assume the droplet is a spherical cap and are only accurate for small droplets (<5 µL for water) and low contact angles where gravity is negligible [35]. The Tangent method offers flexibility for non-axisymmetric drops or when a needle remains in the droplet, but it can be more subjective and less precise than whole-shape fitting methods [35].

Significance of Dynamic Angles and Hysteresis

Static contact angle measurements provide a snapshot of wettability, but real-world surfaces often exhibit contact angle hysteresis—the difference between the advancing (θA) and receding (θR) angles [34] [36]. This hysteresis is a critical parameter, as it quantifies surface heterogeneity and roughness. The Wilhelmy plate method directly measures this hysteresis during the immersion-emersion cycle [34]. In optical methods, dynamic angles are assessed by adding/removing liquid to expand/contract the droplet base, or by using the tilting plate method [30]. Understanding hysteresis is essential for applications involving moving liquid fronts, such as coating processes, lubrication, and the performance of self-cleaning surfaces.

In surface science, particularly for optical cleanliness research, the water contact angle (WCA) serves as a crucial, non-destructive indicator of surface wettability and chemical cleanliness. A contact angle is defined as the angle formed between a liquid surface and a solid surface at their point of contact, quantifying the wettability via the Young equation [16] [15]. For optical applications, even microscopic contamination or surface energy variations can significantly impact performance, making precise contact angle measurement indispensable. The fundamental challenge, however, lies in the fact that optical components are rarely ideal flat planes; they encompass a spectrum of geometries from flat lenses and prisms to curved mirrors and complex sculptured surfaces. Selecting an inappropriate measurement method for a given geometry can yield inaccurate data, leading to incorrect conclusions about surface cleanliness or coating efficacy. This guide objectively compares the performance of various contact angle measurement techniques across flat, curved, and complex optical geometries, providing researchers with the experimental protocols and data needed to make informed methodological choices.

Fundamental Principles and Measurement Methods

The core principle of contact angle measurement is based on the equilibrium of interfacial tensions at the solid-liquid-vapor boundary, described by the Young equation: γSG - γSL - γLGcosθC = 0, where γ represents the interfacial tensions between solid (S), liquid (L), and gas (G) phases, and θC is the equilibrium contact angle [15]. Real-world surfaces exhibit contact angle hysteresis, the difference between the advancing (maximal) and receding (minimal) contact angles, which provides additional information about surface heterogeneity and roughness [15].

Several established methods exist for measuring these angles, each with unique strengths and limitations, which become critically important when dealing with non-flat geometries.

- Sessile Drop: This is the most common method, where a droplet is placed on a solid sample and imaged with a high-resolution camera. The contact angle is then determined automatically by software [39]. It provides a static contact angle and is ideal for quality control and surface energy calculations.

- Needle/Tilting Methods: These dynamic methods measure advancing and receding contact angles. In the needle method, droplet volume is increased or decreased to move the contact line [39]. In the tilting method, the substrate is tilted until the drop moves, allowing measurement of both angles and the roll-off angle [39] [40]. These are crucial for studying superhydrophobic surfaces [41] [39].

- Wilhelmy Plate: This force-based method uses a sensitive balance to measure the force exerted on a sample as it is immersed in or withdrawn from a liquid. It provides an average advancing and receding contact angle for the entire immersed surface [39] [40].

- 3D Contact Angle: A newer method that reconstructs a digital spatial image of the drop from top-view reflections and laser measurements, eliminating the need for manual baseline identification [42].

- Captive Bubble: Used for solid-liquid-liquid systems or superhydrophilic surfaces, this method involves measuring the contact angle of an air bubble on a surface immersed in liquid [39].

Comparative Analysis of Methods for Different Surface Geometries

The accuracy of a contact angle measurement is highly dependent on the match between the measurement technique and the substrate geometry. The following sections and comparative table detail the performance, advantages, and limitations of each method in the context of flat, curved, and complex surfaces.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Contact Angle Methods for Different Optical Geometries

| Measurement Method | Optimal Geometry | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Typical Accuracy/Precision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sessile Drop (Standard 2D) | Flat, homogeneous surfaces [43] | Simple setup; quick; non-destructive; wide industry adoption [16] [39] | Baseline errors on curved/complex surfaces [43] [42]; assumes axisymmetric drop | Varies; highly dependent on operator and baseline definition |

| Sessile Drop (with Advanced Fitting) | Gently curved, extruded surfaces [43] | Does not require a priori information on surface tension or drop volume [43] | Complex image processing; requires multiple viewpoints for 3D surfaces | MAE of 0.8° for θ < 160° on smooth surfaces [43] |